Published on The Commoner, 15 February 2024

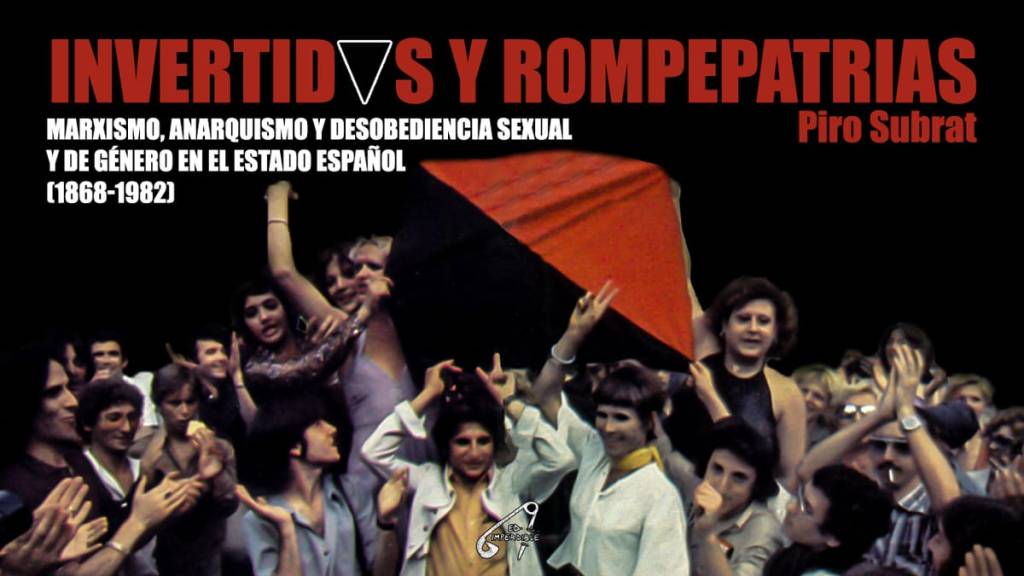

Your book, Invertidos y Rompepatrias (“Queers Wreck the State,” 2019), presents an impressive panorama of sexual and gender dissent in the Spanish State during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although you cover LGBTQ+ history during the Second Republic (1931–9), the Spanish Civil War (1936–9), and the Franquist dictatorship (1939–1975), the majority of the book’s chapters have to do with the “Transition” to formal democracy (1976–1982) following Francisco Franco’s death. There are also additional chapters available on your blog about more recent history, covering themes like anti-fascism, lesbian feminism, HIV/AIDS, and new films and literature.

Could you tell us about your hopes and dreams for the book?

Piro: The first thing that I should clarify in response to this question is that my personal life and political militancy in anarchist spaces, and in spaces of sexual and gender dissent, have played a very important role. I keep this in mind for almost everything I do.

Beyond this, my life’s passion is history, and to analyze and investigate it has always served me well.I believe that it is super-important that we know our history, as it is vital for the strengthening of the present. Moreover, it helps us to have solid references to focus on, so as to press on with our own lives and struggles. It’s not the same if you think that you are alone in the world, carrying on a given struggle, when other people are also involved in a similar way. Equally, it’s not the same if you know that other people—who are very similar to you in terms of sexual orientation, gender identity, and political ideology—struggled along the same lines in the past in your very territory, or in others with which you have certain cultural empathy.

All of this, applied to LGBTQ+ politics in the Spanish State, implied taking on this book project, given that this intersection had been under-investigated, and considering that this relationship is essential for understanding our present. This lapse is due to the fact that the majority of Spanish LGBTQ+ historiography has been monopolized by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), which is the main social-democratic (or post-social-democratic) party in Spain. Furthermore, the PSOE is one of the parties which made a deal with the Franquist elites at the end of Franco’s dictatorship to ensure the Transition Agreement—the very source of the political regime that we have lived and suffered in the Spanish Kingdom since 1978. Given this trajectory, it would be easy for those who don’t know Spanish politics very well to overlook that this party has very specific interests when it comes to historiography. What is more, since the 1990’s, the PSOE has dedicated itself to infiltrating, capturing, and manipulating important parts of the mainstream LGBTQ+ movement. This has granted it a hegemony which it has used to discredit, hide,and even expel from its ranks individual or collective proposals to lay out sexual and gender dissidence from anti-capitalist perspectives.

Applied to Spanish LGBTQ+ historiography, this means that—although it seems to me essential—we missed having a detailed description of the process whereby Marxism and anarchism in Spain passed within 3-4 years or fewer from being overall homophobic to being driving forces for vital changes in the struggle for sexual liberation. These radical mechanisms of social change have been much more important than the PSOE, which after all ended up taking on a leadership role. In the same way, within the construction of LGBTQ+ historical memory, the PSOE’s hegemony has marginalized the collectives and proposals that recommended the deepening of the then-ongoing social revolution, rejected any compromise with Franquism, and openly acknowledged that sexual liberation and capitalism are incompatible.

In this sense, my objectives in writing this book always were, and continue to be, to illuminate and make visible all these political proposals and complicated processes that have led up to the present, and to indicate which forces have been able to manipulate history, and toward what ends, while offering some solid and admirable references to those people who at present continue the struggle against capitalism and heteropatriarchy.

Please tell us a bit about the LGBTQ+ history of Barcelona, which is known for being and having been something of a European capital for the community.

Is this an older, Mediterranean San Francisco?

It’s not wrong to call Barcelona a “San Francisco” of the old age, given that there’s no doubt that it was the main space for sexual dissidence in Europe. This is well-supported by the press and historical testimony. Sadly, Berlin is my witness, given that the enormous environment for sexual and gender dissent in this city (much greater than in Barcelona) was assaulted and destroyed in the first months of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

During the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–30), despite the fact that homosexuality was criminalized in 1928, one-off parties took place in the Barrio Chino (“Chinese Quarter”) of Barcelona and in bourgeois homes on the periphery of the city, while in 1926, La Criolla, the main café for gays and cross-dressers, opened its doors. After 1931, with the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, the number of spaces that accepted drag shows, cross-dressing sex-workers, and the presence of dissent in the streets exploded, such that two more spaces opened: Cal Sagristà, and Barcelona de Noche.

This doesn’t mean that the Republic favored sexual dissidence, as is sometimes suggested in the historiography. In reality, this was a regime that promoted homophobia, criminalized non-reproductive sexual relations in its penal code, and approved special laws that could be used (and were used) against homosexuals. This includes the Law on Vagrants and Criminals, which was subsequently employed by Franco. In the case of Barcelona, city hall prepared an urban plan to destroy the whole neighborhood of Raval (otherwise known as the Chinese Quarter), rationalizing this course of action with reference to the degeneration that supposedly existed there. Plus, the police units of the Republic and of the recently created Government of Catalunya carried out homophobic raids in the neighborhood.

Even so, the Republic did see a relaxation of repression at all levels, including sexual, given that in the preceding decades, such repression had been overwhelming, with the Catholic Church in charge. Given the Republican abolition of a multitude of monarchical laws, the displacement of the Church as the political leadership, and the hopes for freedom held by a great deal of the population (many concentrated in Barcelona), the creation of public spaces and new dynamics of sexual and gender dissent took off. Despite public condemnation in the press, emanating from all political actors, this progress could not be held back by the regime.

Furthermore, the fact that Barcelona is a port city had some influence, too: the Chinese Quarter is very close to the port, and we know that sailors need sexual contact when they disembark in cities, and they often pay for it, even and especially when (as it often was) not heterosexual. Photos including sailors are habitual finds in the visual documentation of the Barcelona context. Also, although this is more difficult to research, there was migration to Barcelona on the part of many European sexual dissidents from France, Italy, Britain, and particularly Germany after 1933. Many of them had pertained to left-wing organizations and joined their equivalents within the Catalan context. Some spied on groups that supported Nazi Germany…

Equally, following the approval of the Law on Vagrants and Criminals in August 1933, the Barcelona environment became reduced, and there were people who had to flee to other cities of the State, such as Valencia, given that in these locations, there was less repression and, indeed, some gay-friendly spaces. In 1934 and 1935, the right wing governed the Republic, and this meant greater social and political control in Barcelona, which translated to the persecution of homosexuals and sex-workers in the Chinese Quarter, with more raids… Then, this repression was eased with the arrival of the Popular Front in February 1936, not only because its politics were less restrictive, but also because its victory was seen as the moment in which social, sexual, and general revolutions would have to be made. Although LGBTQ+ people often didn’t fit into this project, to subjugate them was not a priority. The same year, actually, Barcelona de Noche opens its doors. But this only lasted for a bit, given the start of the Spanish Civil War, the worsening of inflation and hunger, and the beginning of the decline of the gay bars and overall environment. The Chinese Quarter was punished for this reason. In fact, the fascist air forces often targeted it, and during one of these air raids in 1938, La Criolla was bombed and entirely destroyed. This is not to mention that, with the arrival of the fascist troops at the beginning of 1939, this European experience died off, only to be reborn some years later with new spaces, dynamics, and locations. Still, the Chinese Quarter continued to be, as it is today, a reference-point for sexual and gender dissent.

I was a bit surprised to read in Invertidos y Rompepatrias about the pathologization of homosexuality by many Iberian anarchists, who supposedly supported free love (28, 52–6). Frankly, I find it incredible that certain anarchist luminaries have stigmatized non-heterosexual dimensions of the libido as a central focus of their eugenicist campaigns to achieve what they considered to be “public health.” Likewise, the Mexican anarcho-communist Ricardo Flores Magón despised LGBTQ+ people, despite being considered a feminist at the same time.

Without contemplating the cross-over with the homophobia incited by hegemonic Spanish traditions, both monarchical and religious (20), it is almost as though these “freedom-fighters” agreed with present-day tendencies that promote the ill-named “conversion therapy,” which constitutes psychological and sexual torture of queer people.

I think we should contextualize these proposals within their historical times, given that these “conversion therapies” (which I believe began to be called this way in the 1950’s and 1960’s, at the peak of the popularity of behaviorism in psychology) were the most progressive option on hand in Europe a century ago. The alternatives promoted by the Church and the conservative (and not so conservative) political class were detainment, imprisonment, murder, or social isolation, such that these leftists used the tools available to them, applying them to what was considered a social problem. We have to consider the context of viewing science, including medicine and psychiatry, as liberatory elements within the context of societal secularization and liberation from the overwhelming power of the Church. Nowadays, it might be more difficult to understand this position, because science doubtlessly serves power, having little liberatory potential, but then, it was seen as a counter-power to the traditional elites, who accordingly opposed its spread among the proletariat and in political debates. At this time, science had not yet been adapted and integrated to serve ruling-class interests, as would occur in the following decades.

Certainly, I do not wish to rationalize these reformers’ disregard for homosexuality. There were people at this time, who—it must be said—were involved in anti-capitalist, anarchist, and Marxist movements in Europe who openly supported homosexuality and its decriminalization, without calling for psychiatric or medical intervention. This took place more in Central Europe than in the Iberian Peninsula, although such voices were heard here, and such views were also held here, although less frequently and more covertly.

Ultimately, what I want to say is that the combination of eugenicist, psychiatric, and medical proposals as the most progressive alternative at the time, on the one hand, and the lack of eminent voices supportive of homosexuality on the other led to this disastrous mix of pathologizing and therapeutic proposals to cure homosexuality as the most advanced option then available. It may seem absurd to us now, but to say anything along these lines then implied that you would be accused of being gay and insulted, because you were requesting decriminalization, and of course, that’s something for queers. At this time, the right and far-right were less focused on trying to cure homosexuality.

In the case of anarchism, the idea that the State can never improve matters, but rather always worsens them, entered the fray. In other words, the assumption was that criminalizing homosexuality exacerbated the situation, thus creating more homosexuality and more gays. Plus, the eugenicist theories that were then blowing up came hand-in-hand with naturism (then all the rage in the anarchist world) and free love. These were the best alternative then accessible to libertarians, who mostly followed the opinions of established Iberian doctors, rather than those of Èmile Armand, Magnus Hirschfeld, Havelock Ellis, the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin, or the Institute for Sexual Hygiene in Moscow.

Feminists at this time did not present themselves as allies of homosexuals in the least, and the fact that Flores Magón had declared himself a feminist while demonizing homosexuality and wielding homophobia against political rivals (something that was regular practice at the time in Mexico and throughout much of the world) does not really surprise me.