Check out my recent conversation on Thomas Wilson Jardine’s podcast Ideologica Obscura about my review of Mohamed Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism on The Commoner:

Posts Tagged ‘Ahmet Kuru’

Conversation on Modern Islamic Anarchism

September 21, 2023Tags:Afghanistan, Ahmet Kuru, anarcha-Islām, anarchism, Bashar al-Assad, Circassians, current events, Gilbert Achcar, history, Ideological Obscura, Iran, Islam, itjihad, Mahsa Amini, Modern Islamic Anarchism, Mohamed Abdou, NATO, Pseudo-Anti-Imperialism, Qatar, Russia, Salafism, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Taliban, Thomas Wilson Jardine, Ukraine

Posted in 'development', Afghanistan, Algeria, anarchism, audio, book reviews, China, displacement, Egypt, Europe, fascism/antifa, history, imperialism, Iran, literature, Revolution, Syria, U.S., Ukraine, war | Leave a Comment »

Islamic Anti-Authoritarianism against the Ulema-State Alliance

April 5, 2023Abbas al-Musavi, The Battle of Karbala

The second part in a series on Islam, humanism, and anarchism. This review includes an alternate perspective by Jihad al-Haqq.

First published on The Commoner, 5 April 2023. Shared using Creative Commons license. Feel free to support The Commoner via their Patreon here

Building on my critical review of Mohamed Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism (2022), this article will focus on Ahmet T. Kuru’s Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment (2019). Here, I will concentrate on Kuru’s study of Islam, history, and politics, focusing on the scholar’s presentation of the anti-authoritarianism of the early Muslim world, and contemplating the origins and ongoing oppressiveness of the alliance between ulema (religious scholars) and State in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). I will examine Kuru’s analysis of the “decline thesis” about the intellectual, economic, and political counter-revolutions that led Muslim society to become dominated by military and clerical elites toward the end of the Golden Age (c. 700–1300); briefly evaluate the author’s critique of post-colonial theory; and contemplate an anarcho-communist alternative to Kuru’s proposed liberal strategy, before concluding.

Perhaps ironically, Kuru may uncover more Islamic anti-authoritarianism than Abdou does in Islam and Anarchism. Marshaling numerous sources, Kuru clarifies that a degree of separation between religion and the State existed in Islam’s early period; that ‘Islam emphasizes the community, not the state’; and that ‘the history of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates was full of rebellions and oppression.’ In fact, the Umayyad dynasty, which followed the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661) that itself had succeeded the Prophet Muhammad after his death, generally lacked religious legitimation, given that its founders persecuted the Prophet’s family during the period known as the Second Fitna (680–692) [1]. Such sadism was especially evident at the momentous battle of Karbala (680), at the conclusion of which the victorious Umayyad Caliph Yazid I murdered the Imam Hussein ibn Ali, grandson of the Prophet and son of the Rashidun Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib, together with most of his relatives [2]. Shi’ites mourn these killings of Hussein and his family during the month of Muharram, considered the second-holiest month of the Islamic calendar after Ramadan. Currently being observed by Muslims across the globe, Ramadan marks the first revelation of the Quran to Muhammad in Jabal al-Nour (‘the mountain of light’) in the year 610. (For an artistic representation of the latter event, see the featured painting from the Hamla-yi Haidari manuscript below.)

Politically speaking, early Muslims rejected despotism and majesty and emphasized the importance of the rule of law, such that ‘traditional Muslim[s were] suspicio[us] of Umayyad kingship’ [3]. Following the Mutazilites, the Iranian revolutionary Ali Shariati claimed the fatalist belief in ‘pre-determination,’ which was encouraged by the orthodox theologian Ashari, to have been ‘brought into being by the Umayyids’ [4]. Along similar lines, in the Quran it is written, ‘if one [group of believers] transgresses against the other, then fight against the transgressing group,’ while one of the Prophet Muhammad’s ahadith (sayings) declares that the “best jihad is to speak the truth before a tyrannical ruler’[5]. During the time of Muhammad and the Rashidun Caliphs, hence, Islamic politics were rather progressive, for the nascent faith’s founders rejected both oppressive authority, whether exercised locally in Arabia or afar in the Byzantine Empire, and the injustice of the Brahmin caste system. In this vein, all founders of the four Sunni schools of law (fiqh), and some early Shi’ite imams, refused to serve the State. In retaliation, they were persecuted, imprisoned, and even killed [6].

During the Abbasid Caliphate, radical freethinkers such as the physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 854–925) and Ibn Sina (980–1037) made breakthroughs in medical science, while the polymath Biruni (973–1048) advanced the field of astronomy, just as al-Razi and Biruni respectively criticized religion and imagined other planets. Mariam al-Astrulabi (950–?) invented the first complex astrolabe, which had important astronomical, navigational, and time-keeping applications. Plus, Baghdad’s House of Wisdom boasted a vast collection of translations of scholarly volumes into Arabic, and a number of hospitals were founded in MENA during the Abbasid and Mamluk dynasties. Farabi (c. 878–950) emphasized the philosophical importance of happiness, Ibn Bajja (c. 1095–1138) likewise stressed the centrality of contemplation, and Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) made critical contributions to sociology through his insights into asabiyya, or group cohesion. Perceptively, Ibn Khaldun declared that the ‘decisions of the ruler […] deviate from what is right,’ while concurring with some of the most radical Kharijites in holding that the people would have no need for an imam, were they observant Muslims [7].

At the same time, Kuru explains that Islam’s Golden Age (c. 700–1300)—which allowed for the birth of a freer scholarly, political, and commercial atmosphere in the Muslim world, relative to Western Europe—was driven by a ‘bourgeois revolution’ of mercantile capitalism, to which Islam itself contributed [8]. With their private property and contracts ensured, as stipulated by the Quran and Prophet Muhammad’s Medina Charter (622–624), Muslim merchants could accumulate the capital with which to maintain financial, political, and intellectual independence from the State. Indeed, in contrast to the clerics who have served the authorities since the medieval congealing of the ulema-State, most Islamic scholars from this period worked in commerce, thus making possible their patronage of creative thinkers and scientists [9]. While the dynamism of dar al-Islam (the world’s Muslim regions)produced renowned intellectuals like al-Rawandi, al-Razi, Farabi, al-Ma’arri, Ibn Sina, Ibn Khaldun, and Ibn Rushd, among others, freethinking in the West was simultaneously stifled by religious and military elites. In this light, Kuru insightfully compares Islam’s Golden Age to the subsequent European Renaissance, whose coming was indeed facilitated by scholarship from and trade with the Muslim world [10].

The Decline Thesis, and an Anarchist Alternative

Soon enough, however, the ‘[p]rogressive atmospheres’ created by Islam would yield to reaction [11]. With the proclamation in 1089 of a decree by the Abbasid Caliph Qadir outlining a strict Sunni orthodoxy that would exclude Mutazilites, Shi’ites, Sufis, and philosophers, the ulema-State alliance was forged. This joint enterprise created a stifling and stagnating bureaucratic atmosphere opposed to progress of all kinds. Internally, this shift was aided by the eclipse of commerce by conquest, looting, and the iqta system—a feudal mechanism whereby the State distributed lands to military lords and in turn expanded itself through taxes extracted from peasant labor. Additionally, the eleventh-century founding of Nizamiyya madrasas, which propagated Ashari fatalism and stressed memorization and authority-based learning, was decisive for this transformation. Externally, the violence and plundering carried out by Crusaders and Mongols against the Muslim world led to further marginalization of scholars and merchants on the one hand, and deeper legitimization of military and clerical elites on the other [12].

Through comparison, Kuru contemplates how this joint domination by ulema and State—characterized by bureaucratic despotism, State monopolies, and intellectual stagnation—mimics the backwardness of Europe’s feudal societies during the Dark and Middle Ages. Still, just as anti-intellectualism, clerical hegemony, and political authoritarianism are not inherent to Judaism, Christianity, or Western society, this reactionary partnership is not innate to Islam either, considering the remarkable scientific, mathematical, and medical progress made during Islam’s early period. Only later did the combination of Ghazali’s sectarianism, Ibn Taymiyya’s statist apologism, and the Shafi jurist Mawardi’s centralism result in the consolidation of Sunni orthodoxy and despotic rule. Indeed, Kuru traces the germ of this noxious ulema-State alliance to the political culture of the Persian Sasanian Empire (224–651), which prescribed joint rule by the clerics and authorities. In this sense, the ‘decline thesis’ about the fate of scholarship and freethinking in Muslim society cannot be explained by essentialist views that define Islam by its most reactionary and anti-intellectual forms [13].

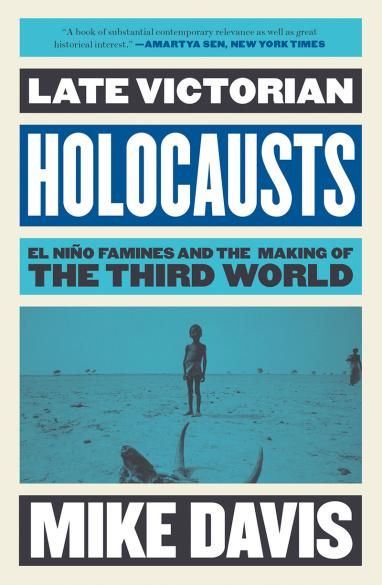

More controversially, Kuru equally concludes that the violence, authoritarianism, and underdevelopment seen at present in many Muslim-majority countries cannot be explained solely by either post-colonial theory or a primary focus on Western (neo)colonialism. This is because post-colonial writers, like Islamists, discourage a critical analysis of the “ideologies, class relations, and economic conditions” of Muslim societies, leading them to overlook, and thus fail to challenge, the enduring presence of the ulema-State alliance [14]. In parallel, the caste system persists in post-colonial India, while “British and German scholars did not invent caste oppression,” as much as fascists across the globe have been inspired by it [15]. At the same time, according to the late Marxist scholar Mike Davis, European imperialism, combined with excess dryness and heat from the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon, led to famines that killed between 30 and 60 million Africans, South Asians, Chinese, and Brazilians in the late nineteenth century. The Indian economist Utsa Patnaik estimates that British imperialism looted nearly $45 trillion from India between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries.

Currently, bureaucratic authoritarianism in MENA is financed by the mass-exploitation of fossil fuels, which finances the State’s repressive apparatus, hinders the independence of the workers and the bourgeoisie, and disincentivizes transitions to democracy [16]. Certainly, the West, which runs mostly on fossil fuels, and whose leaders collaborate with regional autocrats, is complicit with such oppression, whether we consider its long-standing support for the Saud dynasty (including President Biden’s legal shielding of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman against accountability for his murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi), more recent ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the past alliance with the Pahlavi Shahs, or the love-hate relationships with Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi. The US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, launched twenty years ago, killed and displaced similar numbers of people as Assad and Putin’s counter-revolution has over the past twelve years.

Overall, Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment helps illuminate the religious, political, and economic dimensions of the legacy of the authoritarian State in MENA. Moving forward, Kuru’s proposed remedy to the interrelated and ongoing problems of authoritarianism and underdevelopment in Muslim-majority countries is political and economic liberalisation. The author makes such liberal prescriptions based on his historical analysis of the progressive nature of the bourgeoisie, especially as seen during the Golden Age of Islam and the European Renaissance. As an alternative, he mentions the possibility that the working classes could help democratize the Muslim world, but notes that they are not an organized force [17]. Moreover, in a 2021 report, ‘The Ulema-State Alliance,’ Kuru clarifies that he is no proponent of ‘stateless anarchy,’ as might be pursued by anarcho-syndicalist or anarcho-communist strategies.

Yet, it is clear that empowering the bourgeoisie has its dangers: above all, global warming provides an especially stark reminder of the externalities, or ‘side-effects,’ of capitalism. Plus, at its most basic level, the owner’s accumulation of wealth depends on the rate of exploitation of the workers, who cannot refrain from alienated labor, out of fear of economic ruin for themselves and their loved ones. This is the horrid treadmill of production. As the critical theorist Herbert Marcuse recognized, capitalism is an inherently authoritarian, hierarchical system [18]. Although bourgeois rule may well allow for greater scientific, technical, and scholarly progress than feudal domination by clerical-military elites, whether in Europe, MENA, or beyond, the yields from potential advances in these fields could be considerably greater in a post-capitalist future. Science, ecology, and human health could benefit tremendously from the communization of knowledge, the overcoming of fossil fuels and economic growth, the abolition of patents and so-called ‘intellectual property rights,’ the socialization of work, and the creation of a global cooperative commonwealth. Considering how Western and Middle Eastern authorities conspire to eternally delay action on cutting carbon emissions as climate breakdown worsens, both Western and MENA societies would gain a great deal from anti-authoritarian socio-ecological transformation.

In sum, then, I reject both the ulema-State alliance and Kuru’s suggested alternative of capitalist hegemony—just as, in mid-nineteenth-century Imperial Russia, the anarchists Alexander Herzen and Mikhail Bakunin rebuked their colleague Vissarion Belinsky’s late turn from wielding utopian socialism against Tsarism to espousing the view that bourgeois leadership was necessary for Russia [19]. In our world, in the near future, regional and global alternatives to bourgeois-bureaucratic domination could be based in working-class and communal self-organization and self-management projects, running on wind, water, and solar energy. Such experiments would be made possible by the collective unionization of the world economy, and/or the creation of exilic, autonomous geographical zones. Despite the “utopian” nature of such ideas, in light of the profound obstacles inhibiting their realization, this would be a new Golden Age or Enlightenment of scientific and historical progress, whereby a conscious humanity neutralized the dangers of self-destruction through raging pandemics, global warming, genocide, and nuclear war.

Conclusion: For Anarcho-Communism

In closing, I express my dynamic appreciation for Kuru’s Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment, which aptly contests both essentialist and post-colonialist explanations for the violence, anti-intellectualism, and autocratic rule seen today in many Muslim-majority societies. Kuru highlights the noxious work of the ulema-State alliance to impose Sunni and Shi’i orthodoxies; legitimize the authority of the despotic State; and reject scientific, technological, social, and economic progress. Keeping in mind the anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker’s framing of anarchism as the “confluence” of socialism and liberalism, I welcome the author’s anti-authoritarian proposals to revisit the freethinking of the Golden Age of Islam and liberalise the Muslim world, but contest Kuru’s apparent pro-capitalist orientation. In this vein, the writer’s recommendations could be radicalized to converge with the “Idea” of a global anarcho-communist movement that rejects clerical and political hierarchies as well as capitalism, militarism, and patriarchy, in favor of degrowth, a worldwide commons, international solidarity, mutual aid, and working-class and communal self-management of economy and society.

Western Colonialism and Imperialism – Jihad al-Haqq

Whilst Kuru’s historical description of the ulema-state alliance usefully describes the historical oppressions of Muslim-majority nations, it does not explain their continued existence. Especially not in the face of the Arab Spring and, as Kuru himself cites, the vast popularity of democracy amongst Muslims (page xvi, preface). Indeed, a name search reveals that the term ‘Arab Spring’ is used only four times throughout the entire book—three of those times are in the citations section. It is stunning to have a book talking about Islam, authoritarianism, and democracy, without mentioning the momentous event of the Arab Spring. That is, the concept of the ‘ulema-state alliance’ is useful in describing the internal form of social oppression in Muslim-majority societies, but it does not explain why and how those forms continue to exist, which is primarily due to Western imperialism.

Ahmet Kuru’s discussion regarding the ulema-state alliance seems geared towards explaining the question of why Muslim-majority countries are less peaceful, less democratic, and less developed. The question is primarily a political-economic question, not a question of faith, and thus requires a political-economic answer, which he acknowledges. However, he contends that Western colonialism is not a primary material cause for the unrest and destitution in Muslim majority nations; rather, it is the ulema-state alliance. This is a strange argument, for several reasons.

Firstly, his criticism of postcolonial writers is a strawman. The main hypothesis of postcolonial writers is that oppression in Muslim majority nations, whatever form it takes (including the ulema-state alliance), is primarily financed and armed by Western powers and Gulf nations; it is to explain the prevention of democracy in Muslim-majority nations.

He writes:

‘The anti-colonial approach has some power in explaining the problem of violence in certain Muslim countries. But Western colonization/occupation is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for violence. It is not sufficient, as there have been non-Muslim and Muslim countries that were colonized or occupied but where many influential agents did not choose to use violence. Such leading figures as Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–98) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), for example, adopted a position of non-violence against British colonization in India. Western colonization/occupation is not a necessary condition either, because several non-Western countries and groups have fought each other for various reasons. The long list includes the Iran-Iraq War and recent civil wars in several Arab countries. In Turkey, violence has continued between the Turkish state and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) for more than three decades, regardless of whether Turkey was ruled by secularists or Islamists, and regardless of whether the PKK defended or renounced Marxist-Leninist ideology.’

He says that Western colonization and occupation is not a sufficient condition for the violence in Muslim-majority countries, since other countries under the same conditions did not choose to use violence. However, this flies in the face of the history of decolonial movements, since many other countries other than the Muslim-majority ones did choose violence as a method, while several Muslim-majority thinkers did and do advocate non-violence. Decolonization as a process in each country cannot be easily separated into a non-violent and violent category, such as in Indian decolonization being entirely non-violent and decolonization in Algeria being entirely violent, as you will find both non-violent and violent currents in each country advocating decolonization. Moreover, whether a decolonial process is more violent or not overwhelmingly depends on other socio-political factors: the British did not let go of India because they suddenly found enlightenment about the wrongdoing of their ways, and it would be difficult to say that Indian decolonization would not have turned more violent if the British had not ended up letting go of the Raj. We must also question the assumption that colonialism ended at all: there have been many convincing works that effectively argue that instead of colonisation ending, we have simply moved to another form of colonisation facilitated through nation states, rather than overt conquest. Parts of these works make very hard to dismiss cases, backed up by historical records, that show that much of the violence that exists in Global South countries, including Muslim-majority ones, is not due to internal cultural or social institutions, but due to the financing and arming of violent forces in the country. The existence of destitution can be directly linked to such Western-supported authoritarians in these societies.

The United States, for example, armed and supported the dictator Suharto in Indonesia, who is one of the worst mass murderers of the 20th century, against the popular Communist Party in Indonesia. The US is also one of Saudi Arabia’s greatest allies, with Saudi Arabia likely having the most institutionalized form of the ulema-state alliance. William Blum’s classic Killing Hope goes through many details of the various democracy movements throughout the world which the United States has crushed, including in Muslim-majority nations. Perhaps amazingly, the list of examples Kuru uses to support the argument that Western imperialism cannot be stated to be a necessary condition of violence do indeed have a traceable Western influence. Furthermore, the phenomenon of imperialism, which is separate from colonialism and the main focus of many postcolonial writers, does not seem to factor into his analysis.

Moreover, violence as a response to colonisation is almost a universal given—it is not the expression of culture anymore than a person being attacked and choosing to fight back is an expression of ideology. Revolutionary violence is a response to violence: the colonised are forced to be violent in response to the violence waged upon them, regardless of what culture they have, and all people have the right to violence for self-defense. For that, I do not think a detailed discussion is required.

The thesis which Kuru is attempting to argue here is that both revolutionary violence and internal violent structures are expressions of the same structures within Muslim-majority nations that cause more violence to happen. I do not believe this conclusion is tenable, since, on the one hand, revolutionary violence is waged defensively in response to colonialism, and on the other, the internal violence of current Muslim-majority nations do have a traceable Western influence: it would be difficult to argue that Iraq today would be as violent as it is if the United States had not diplomatically and militarily supported the rise of Saddam Hussein, and had not invaded Iraq in 2003. Both of these sorts of violence do not have the same social, political, and economic roots, and therefore cannot be classed as expressions of the same socio-cultural phenomenon.

Kuru’s answer to the continued existence of oppression in the Middle East is economic and political liberalisation; however, as demonstrated with the Arab Spring, the idea of political liberalisation will not be tolerated by the various monarchies and dictatorships of the Middle East, who are largely supported and armed by the United States. Furthermore, Kuru’s proposal of political and economic liberalisation is not really liberalisation—at the very least, not liberalisation if we understand “liberalisation” to mean liberating. He proposes the introduction of a new class of economic capitalist elites, which is hardly an improvement from the ulema-state alliance—never mind that Middle Eastern nations are already economically liberalised. While Kuru’s text is useful in discussing the form of historical oppressions, it reaches too far in its concluding theory regarding the continued existence of despotism in the Middle East.

Works Cited

Abdou, Mohamed 2022. Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances. London: Pluto.

Afary, Janet and Kevin B. Anderson 2005. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Hammond, Joseph 2013. “Anarchism.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Eds. Gerhard Bowering et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 36–7.

Kuru, Ahmet T. 2019. Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Malia, Martin 1961. Alexander Herzen and the Birth of Russian Socialism. New York: Universal Library.

Marcuse, Herbert 1968. Negations: Essays in Critical Theory. Boston: Beacon Press.

Quran. Trans. Mustafa Khattab. Available online: https://quran.com. Accessed 13 August 2022.

Ramnath, Maia 2022. “The Other Aryan Supremacy.” ¡No Pasarán! Ed. Shane Burley. Chico, CA: AK Press. 210-69.

Shariati, Ali 2003. Religion vs. Religion. Trans. Laleh Bakhtiar. ABC International Group.

References

[1] Kuru 10-12, 71.

[2] Afary and Anderson.

[3] Kuru 89.

[4] Shariati 32; Kuru 95.

[5] Quran 49:9 (emphasis added); Abdou 201.

[6] Kuru 70-2, 88-9.

[7] Ibid 76-80, 131-2, 134, 139-41, 150; Hammond 36.

[8] Kuru 83-87.

[9] Quran 4:29; Abdou 116; Kuru 73.

[10] Kuru 93, 159-61.

[11] Ibid 116-7.

[12] Ibid 96-102, 126-7.

[13] Ibid xvi-xv, 96-7, 112-16, 146-7, 185-203, 227-235.

[14] Ibid 34, 234.

[15] Ramnath 254.

[16] Kuru 49-53.

[17] Ibid 55n107.

[18] Marcuse 9-11, 18-19.

[19] Malia 353-6.

Tags:Abbasid dynasty, Ahmet Kuru, Ahmet T. Kuru, al-Ma'ari, al-Rawandi, al-Razi, Alexander Herzen, Ali Shariati, anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, ancom, Ashari, authoritarianism, Biruni, Brahminism, Byzantines, capitalism, caste system, decolonization, democracy, Enlightenment, ENSO, Farabi, fiqh, Ghazali, global warming, House of Wisdom, Ibn Bajja, Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Sina, Ibn Taymiyya, Indonesia, Islam, Islamic Golden Age, Islamism, Jabal al-Nour, Javier Sethness, Jihad al-Haqq, Kharijites, Killing Hope, Late Victorian Holocausts, Liberalism, Mamluk dynasty, Mariam al-Astrulabi, Mawardi, Medina Charter, MENA, Mike Davis, Mikhail Bakunin, Muammar Qaddafi, Muharram, Mutazila, Mutazilites, Nizamiyya, PKK, post-colonialism, Prophet Muhammad, Qadir, Ramadan, Rashidun, Renaissance, Rudolf Rocker, Saddam Hussein, Samarkand, Saudi Arabia, Shi'ism, socialism, Sufism, UAE, ulema-State alliance, Umayyad, Umayyad dynasty, Utsa Patnaik, Vasily Vereshchagin, Vissarion Belinsky, WWS

Posted in 'development', Abya Yala, anarchism, book reviews, China, climate catastrophe, displacement, ecology, health, imperialism, Iran, Iraq, Kurdistan, literature, Palestine, reformism, Revolution, Russia/Former Soviet Union, South Asia, Syria, U.S., war | 1 Comment »

Against Orthodoxy and Despotic Rule: A Review of Islam and Anarchism

January 20, 2023

Published on The Commoner, 20 January 2023

The project of advancing anarchist reinterpretations of history and religion is an intriguing and important one. Due to its emphasis on spontaneity, non-cooperation, simplicity, and harmony, Daoism is a religion with anarchist elements, while the Dharma taught by Buddhism is an egalitarian critique of caste, class, and hierarchy, according to the anarcho-communist Élisée Reclus. B. R. Ambedkar, architect of India’s constitution, similarly viewed Buddhism as seeking the annihilation of Brahminism, as crystallized in the Hindu caste system. Xinru Liu, author of Early Buddhist Society (2022), adds that a key part of Buddhism’s appeal has been its emphasis on care and well-being over statecraft and power.

Likewise, Guru Nanak, the visionary founder of Sikhism, proclaimed human equality through his advocacy of langar, a practice that simultaneously rejects caste while building community through shared meals. In parallel, many notable anarchists have been Jewish: for instance, Ida Mett, Aaron and Fanya Baron, Martin Buber, and Avraham Yehuda Heyn, and Murray Bookchin. The Judaic concept of tikkun olam (repairing the world) is activist to the core. Plus, in The Foundations of Christianity (1908), Karl Kautsky highlights the radicalism of Jesus’ message, the communism of early Christianity, and the ongoing struggles of prophets, apostles, and teachers against clerical hierarchies and bureaucracies. Lev Tolstoy, Dorothy Day, and Simone Weil preached Christian anarchism.

What, then, of Islam?

One way of answering this question would be to consider Mohamed Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism (2022). This long-anticipated study is based on the intriguing premises that Islam is not necessarily authoritarian or capitalist, and that anarchism is not necessarily anti-religious or anti-spiritual. To his credit, Abdou does well in highlighting the transhistorical importance of the Prophet Muhammad’s anti-racist ‘Farewell Address’ (632), and in citing humanistic verses from the Quran. These include ‘Let there be no compulsion in religion,’ and the idea that Allah made us ‘into peoples and tribes so that [we] may get to know one another,’ not abuse and oppress each other [1]. The author constructs an ‘anarcha-Islām’ that integrates orthodox Sunni Muslim thought with Indigenous and decolonial critiques of globalisation. He laments and criticizes the supportive role often played by diasporic Muslims in settler-colonial societies like the USA and Canada, through their putative affirmation of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. Although he is a strong proponent of political Islam, Abdou also recognizes that trans-Atlantic slavery had its origin in Muslim-occupied Iberia, known as al-Andalus [2].

That being said, for better or worse, the overall trajectory of Abdou’s argument reflects the author’s orthodox Sunni bias. Even if Sunnis do comprise the vast majority of the world’s Muslim population—and thus, perhaps, a considerable part of Abdou’s intended audience—there is nonetheless a stunning lack of discussion in this book of Shi’ism (the second-largest branch of Islam) or Sufism (an Islamic form of mysticism practiced by both Sunni and Shi’ites). In a new review in Organise Magazine, Jay Fraser likewise highlights the author’s ‘odd choice,’ whereby ‘the Sufi tradition […] receives no mention whatsoever.’ Besides being intellectually misleading for a volume with such an expansive title as Islam and Anarchism, such omissions are alarming, as they convey an exclusionary message to the supercharged atmosphere of the Muslim world.

Islam and Anti-Authoritarianism

At the outset of his book, Abdou proposes that a properly Muslim anarchism should be constructed on the basis of the Quran, the ahadith (the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings),and the sunnah (Muhammad’s way of life) [3]. This is a paradoxically neo-orthodox Sunni approach that overlooks the contributions of both 1) Shi’ites, who place less stress on the sunnah, and 2) several anti-authoritarian and anarchistic Muslim thinkers, individual and collective, who emerged during and after Islam’s so-called ‘Golden Age’ (c. 700-1300). In this sense, although Abdou would follow the ‘venerable ancestors’ (al-salaf al-salih) from Islam’s earliest period, hedoes not discuss Abu Dharr al-Ghifari (?-652), one of the very first converts to Islam. Al-Ghifari was known for his socialist views, and revered by Shia as one of the ‘Four Companions’ of the fourth ‘Rightly Guided’ (Rashidun) caliph, Ali ibn Abi Talib (559-661) [4].

Neither does the author examine the utopian radicalism of the sociologist Ali Shariati (1933-1977), who inspired the Iranian Revolution of 1979 against the U.S.-installed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In writings and lectures, Shariati espoused a ‘red’ Shi’ism that celebrates insurgency and martyrdom, by contrasting this with the ‘black Shi’ism’ instituted by the Safavid dynasty (1501-1734), one of early modernity’s infamous ‘gunpowder empires,’ which forcibly converted most Iranians to Shi’ism while persecuting Sunnis and Sufis [5]. Despite their separation by sect, this is an unfortunate missed connection between Abdou and Shariati, in light of the similarity of their analysis of tawhid, or the allegiance to God as the sole authority (Malik al-mulk) mandated by Islam [6]. (Likewise, monotheistic loyalty is demanded by the Judeo-Christian First Commandment.)

Through his elucidation of ‘Anarcha-Islām,’ which ‘adopts and builds on traditional [Sunni] orthodox non-conformist Islamist thinkers,’ Abdou does consider the revolutionary potential of Shi’i eschatology—crystallized in the prophesized return of the twelfth imam (or Madhi), who is expected to herald world peace—as evidence of an ‘internalized messiah and savior complex’ [7]. It is in the first place paradoxical for an ostensible anarchist to so overlook messianism, and especially troubling when such a Shi’i tradition is ignored by a Sunni Muslim developing an anarcha-Islām. Still, while Abdou pays lip service to the criticism of Muslim clerics, he hardly mentions the theocracy imposed by the Shi’i ulema (religious scholars) who appropriated the mass-revolutionary movement against the Shah for themselves over four decades ago, having spearheaded the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) since 1981.

Even more, in a November 2022 podcast interview on ‘Coffee with Comrades,’ Abdou complains in passing about the ‘mobilization of gendered Islamophobia’ in Iran following the murder by the ‘Morality Police’ of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old Kurdish woman, two months prior for rejecting imposed veiling. Presumably, this is in response to criticism of Islamic hijab by Westerners and Iranians alike, but he does not make clear his opinion of the ongoing youth- and women-led mass-protests that have rocked the country since then. By contrast, members of Asr Anarshism (‘The Age of Anarchism’), based in Iran and Afghanistan, stress in an upcoming interview on The Commoner that the ‘struggle with the clerical class […] constitutes a basic part of our class struggles’ [8].

Likewise, the late Indian Marxist Aijaz Ahmad (1941-2022) openly viewed the IRI’s ulema as ‘clerical-fascist[s],’ while Shariati would have likely considered these opportunistic, obscurantist lynchers as part and parcel of the legacy of ‘black Shi’ism’ [9]. In parallel, the Sri Lankan trade unionist Rohini Hensman takes the IRI to task for its abuse of women, workers, the LGBT community, and religious and ethnic minorities, just as she denounces Iran and Russia’s ghastly interventions in Syria since 2011 to rescue Bashar al-Assad’s regime from being overthrown [10]. Abdou’s lack of commentary on Iran and Shi’ism in Islam and Anarchism is thus glaring.

Furthermore, in the conclusion to his book, Abdou questionably echoes the Kremlin’s propaganda by blaming the mass-displacement of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) into Europe a decade ago exclusively on President Barack Obama’s use of force, presumably against Libya and the Islamic State (IS, or Da’esh)—with no mention of the substantial ‘push factors’ represented by the atrocious crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Syrian, Iranian, and Russian states [11]. Worse, in his interview on ‘Coffee with Comrades,’ the author finds himself in alignment with the neo-Nazi Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke on Syria. Let us quote him at length:

‘It’s so easy for David Duke to come out and say, ‘Well, I’m against the war in Syria!’ Well, how about that: an anti-imperialist stance coming from a white supremacist? Right? Well, of course I don’t agree with him on much of anything else. […].

And again, this is where we have to be very intelligent and very smart. Of course, I feel for my Syrian kin. They are my own blood. But, if you ask me now with regards to Bashar al-Assad, I will say: keep him in power. Why? I’m able to distinguish between tactics and strategy. Unless you have an alternative to what would happen if Bashar was removed, let alone, what would you do with the State: please, please stay at home. Because what you will create is precisely a vacuum for Da’esh [the Islamic State]. You will create a vacuum for imperialism, for colonialism to seep in.’

Abdou here affirms a cold, dehumanizing, and statist illogic that is entirely in keeping with the phenomenon of the pseudo-anti-imperialist defense of ‘anti-Western’ autocracies like Syria, Russia, China, and Iran [12]. In reality, in the first place, both openly anti-Assad rebels and TEV-DEM in Rojava have presented alternatives to the Ba’athist jackboots, and the Free Syrian Army and YPG/SDF forces have fought Da’esh. The YPG/SDF continue to do so, despite facing a new threat of destruction at the hands of the Turkish State and the regime axis. Beyond this, does Abdou believe Russia’s military intervention in Syria since 2015 somehow not to have been imperialist? Millions of displaced Syrians would likely disagree with the idea. We can recommend For Sama, about the fall of Aleppo in 2016, as documentary evidence of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war crimes.

According to Leila al-Shami and Shon Meckfessel, ‘[m]any fascists take Russia’s backing of Assad as reason enough to support him,’ and the global far right is even heartened and inspired by the regime-axis’s ultraviolence and unmitigated cruelty [13]. Indeed, in this vein, for over a decade, Russian State media and their fascist and ‘tankie’ (neo-Stalinist) enthusiasts have blamed the West for problems perpetrated by the Kremlin and its allies themselves—from mass-refugee flows from Syria to genocide in Ukraine. It is therefore disturbing to see Abdou betray anarchism and internationalism by not only reiterating deadly disinformation, but also by openly endorsing Assad’s tyranny.

Sufism and the Ulema-State Alliance

Although Sunni orthodoxy, jihadist revivalism, institutionalized Shi’ism, and secular autocracies are undoubtedly oppressive, Sufism has been misrepresented by many Orientalists as negating these stifling forces. In reality, while some Sufis have ‘preached antiauthoritarian ideas,’ Sufism is not necessarily progressive [14]. Although the Persian thinker Ghazali (1058-1111, above) resigned from teaching at an orthodox madrasa in 1095 to preach Sufism and condemn political authority—only to return to teaching at a similar madrasa late in life—he played a key role in legitimizing the toxic alliance between ulema (religious scholars) and State. Moreover, by affirming mysticism, asceticism, and irrationalism, Sufi sheikhs have often re-entrenched spiritual and sociopolitical hierarchies [15].

Actually, the Janissary shock-troops of the Ottoman Empire belonged to the Bektashi Sufi Order, and the autocratic Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is reported to be part of the Naqshbandi Sufi Order. Furthermore, Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (1703-1762), who inspired the founders of the Deobandi school of Islam—a variant of which the Taliban has imposed on Afghanistan twice through terror—was a Sufi master. On the other hand, so were Nizamuddin Auliya (1238-1325), who advocated a Sufism critical of class divisions and despotism; Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdallah (1844-1885), a Nubian warrior and self-proclaimed Mahdi who spearheaded a jihad against the Ottomans, Egyptians, and British in Sudan; and Imam Shamil (1797-1871), an Avar chieftain who led anti-colonial resistance to Russian conquest of the Caucasus for decades.

In his compelling study of comparative politics, Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment (2019), Ahmet Kuru provides important insights into the historical trajectory of the Muslim world, vis-à-vis Western Europe. He shows how an alliance between the State and ulema was adopted by the Seljuk Empire in the eleventh century, and then inherited and upheld by the Mamluk, Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires, prior to European colonization. Its noxious legacy undoubtedly persists to this day, not only in theocratic autocracies like Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Qatar, and the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), but also in ostensibly secular military dictatorships, such as Syria and Egypt, and electoral autocracies like Turkey. This is despite past top-down efforts to secularize and modernize Islamic society by breaking up the power of the ulema, as Sultan Mahmud II, the Young Ottomans, the Young Turks, and Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) sought to do during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries [16]—notwithstanding the chauvinism and genocidal violence of these Turkish leaders, echoes of which resonate in Azerbaijani attacks on Armenia in September 2022.

In the remainder of the first part of this article, I will review Abdou’s account of anarcha-Islām. The second part will focus on Kuru’s arguments about Islam, history, and politics, tracing the anti-authoritarianism of early Islam, and contemplating the origins and ongoing despotism of the ulema-State alliance.

Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism

In his book, Abdou mixes post-anarchism (an ideology combining post-modernism, post-structuralism, and nihilism) with Islamic revivalism to yield “anarcha-Islām,” a framework which rejects liberalism, secularism, human rights, and democracy almost as forms of taqut, or idolatry [17]. His study thus bears the distinct imprints of the thought of Egyptian jihadist Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), whom he regards as a ‘non-conformist militant conservativ[e]’ [18] (Notably, Qutb has inspired al-Qaeda and the Islamic State). In keeping with the Qutbist view that all existing societies are jahili, or equivalent to the ostensible ‘state of ignorance’ in Arabia before the rise of Islam, Abdou laments and denounces the Saudi ruling family’s commercialization of Mecca and Medina, and makes comments that are not unsympathetic toward the egoist Max Stirner, plus Muhammad Atta and other terrorists [19]. He describes the U.S. as a ‘Crusading society.’

Abdou endorses researcher Milad Dokhanchi’s view of decolonization as ‘detaqutization’ (the iconoclastic destruction of idolatry, or taqut) and condemns the ‘homonationalist and colonial/imperial enforcement of queer rights (marriage, pride) […]’ [20]. Even the mere concept that ‘queer rights are human rights’ is irretrievably imperialist for him [21]. Moreover, he focuses more on violence than social transformation through working-class self-organization—in keeping with an insurrectionist orientation [22]. In sum, the author himself confesses to being an ‘anti-militaristic militant jihādi’ [23].

Through his conventional reliance on the Quran and ahadith and his parallel avowal of anarchic ijtihad (‘independent reasoning’), Abdou mixes the rationalism of Abu Hanifa (699-767) and the Hanafi school of jurisprudence with the orthodox literalism of Shafii (767-820) and Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780-855), the ‘patron saint’ of traditionalists who, together with Ghazali and Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328), pushed for the ulema-State alliance [24].(By comparison, the Taliban has implemented a combination of the Deobandi school, a branch of the Hanafi tradition founded in British-occupied India in the nineteenth century, and Hanbalism, due to heavy influence from Gulf petro-tyrants.)

Considering the apparent risks involved in legitimizing religious fundamentalism, it is unfortunate that Abdou omits discussion of Muslim philosophers like the proto-feminist Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126-1198) and only mentions the Mutazilites—the first Islamic theologians, who espoused liberal-humanist views—and the anarchistic Kharijites in passing [25]. The Kharijites, who arose in the First Islamic Civil War (656-661), rejected the authority of the early Umayyad dynasty (661-750 CE), and even assassinated Ali ibn Abi Talib, the last Rashidun caliph. Some Kharijites rejected the need for an imam altogether [26]. In turn, the Mutazilites advocated reason and moral objectivism, while questioning the theological reliance on ahadith and divine commands. This is despite the mihna, or inquisition, imposed by the caliph Mamun from 833-851 to propagate Mutazila doctrine.

In his book, Abdou goes so far as to claim that ‘anti-authoritarianism [is] inherent to Islām’ [27]. Yet, he omits several important considerations here. For instance, he dismisses that the religion’s name literally translates to ‘surrender’ or ‘submission,’ and ignores that the Quran mandates obedience to ‘those in authority’ [28]. Implicitly channeling the fatalism of the orthodox Sunni theologian Ashari (873-935) over the free will championed by the scholar Taftazani (1322-1390?), Abdou proclaims that ‘[n]othing belongs to our species, including our health, nor is what we “possess” a product of our will or our own “making”’ [29]. The ascetic, anti-humanist, and potentially authoritarian implications of this view are almost palpable: Abdou here asserts that neither our life nor our health is our own, and that we have little to no agency.

Against such mystifications, in God and the State (1882), Mikhail Bakunin describes how organised religion blesses hierarchical authority, while in The Essence of Christianity (1841), Ludwig Feuerbach contests the idea that religious directives are divine in origin, showing that they are instead human projections made for socio-political ends. According to the Persian iconoclast and atheist Ibn al-Rawandi (872-911), in this vein, prophets are akin to sorcerers, God is a human creation, and neither the Quran nor the idea of an afterlife in Paradise is anything special. Therefore, although Abdou claims to disavow authoritarian methods throughout his book, it is unclear how a fundamentalist belief in the divine authority of the Quran can be reasonably maintained without mandating a particularly orthodox approach to religion and politics.

Furthermore, Abdou presents his puzzling view that Islam is anti-capitalist, just as he affirms the faith’s emphasis on property, banking, charity, and market competition—most of which are fundamentally bourgeois institutions [30]. The French historian Fernand Braudel is more blunt: ‘anything in western capitalism of imported origin undoubtedly came from Islam’ [31]. Indeed, Kuru observes that ‘the Prophet Muhammad and many of his close companions themselves were merchants,’ and that the name of the Prophet’s tribe, Quraysh, is itself ‘derived from trade (taqrish)’ [32]. Economic historian Jared Rubin adds that ‘[t]he Arab conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries […] provided security and a unifying language and religion under which trade blossomed.’ Baghdad during the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258) was a riverine commercial hub, with each of its four gates ‘leading outward to the major trading routes’ [33]. In this sense, Islam may have influenced Protestantism, not only due to certain Muslims’ critiques of political authority resonating in the Protestant Reformation, but also due to the two faiths mandating similar work ethics and fixations on profit [34]. That being said, ‘unlike Jesus, Muhammad commanded armies and administered public money’ [35].

Abdou avoids all of this in his presentation of anarcha-Islam. While such lacunae may be convenient, to consider them is to complicate the idea of coherently mixing orthodox Islam with the revolutionary anti-capitalist philosophy of anarchism [36].

As further evidence of Abdou’s confused approach, the author engages early on in outright historical denialism regarding Muslim conquests during the seventh and eighth centuries, which involved widespread erasure of Indigenous peoples, but later block-quotes the poet Tamim al-Barghouti, who contradicts him by referring to these as ‘expansionary wars’ [37]. In one breath, Abdou praises the pedophile apologist Hakim Bey as an ‘influential anarchist theorist,’ and in the next, he asserts that truth regimes are different in ‘the East and Islām,’ compared to the West [38]. Such claims are consistent with the post-modern denial of reality. In Foucault and the Iranian Revolution (2005), Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson convincingly show the risks of this very approach, considering how Michel Foucault’s belief that Iranian Shi’ites had a different ‘regime of truth’ from Westerners led this philosopher not only to uncritically support Khomeinism, but also to legitimize its newfound ulema-State alliance in the eyes of the world [39]. Unfortunately, Abdou’s perspective on the Syrian regime is not dissimilar.

Meanwhile, the author avows Muslim queerness with reference to bathhouse (hammam) cultures and the Maqamat of al-Hariri (see above). He could also have incorporated the hadith al-shabb, which conveys the Prophet’s encounter with God in the beauty of a young man; quoted some of the homoerotic ghazals written by Persian poets like Rumi (1207-1273), Sa’adi (c. 1213-1292), and Hafez (c. 1325-1390); or considered the complaints of Crusaders about the normalization of same-sex bonds in Muslim society [40]. Indeed, the bisexual German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe viewed the meditative recitation of the ‘99 Names’ of God (al-asma al-husna) as a ‘litany of praise and glory’ [41]. Even so, Abdou does not acknowledge or critique the existence of homophobic and lesbophobic ahadith, much less contemplate how the Quranic tale of the Prophet Lut associates gay desire with male rape, thus closing off the possibility of same-sex mawaddah (or love and compassion) [42]. Instead, he cites an article from 2013 on the role of Islam in the treatment of mental illness, which explicitly perpetuates the reactionary view of homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder, without comment or condemnation [43]!

In contrast, researcher Aisya Aymanee Zaharin deftly elaborates a progressive revisionist account of queerness in Islam that is critical of social conservatism and heteronationalism among Muslims, particularly in the wake of European colonialism and the Wahhabist reaction, led by Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Zaharin builds her case from the vantage point of an essentialist belief in the naturalness of same-sex attraction, the importance of human dignity and affection within Islam, and supportive Quranic verses mentioning how Allah has ‘created for you spouses from among yourselves so that you may find comfort in them. And He has placed between you compassion and mercy’ [44].

Overall, Abdou endorses the classic shortcomings of post-colonialism and post-left anarchism in his conclusion. Here, he simultaneously provides an overwhelmingly exogenous explanation for the rise in Islamic-fundamentalist movements, denounces the ‘destructive legacy of liberalism,’ condemns Democrats’ ‘obsession’ with Donald Trump, and provides discursive cover for Assad and Putin’s crimes [45]. His downplaying of the dangers posed by Trump is clearly outdated and ill-advised. Although Abdou is right to criticize certain factors external to MENA, such as Western militarism and imperialism, he does not convincingly explain how anarcha-Islam can overcome existing authoritarianism and prevent its future resurgence, whilst simultaneously committing itself to the authority of a particular theology. Indeed, Abdou at times prioritises fundamentalism over progressivism and libertarian socialism—thus proving anarchist scholar Maia Ramnath’s point that the ‘same matrix […] of neoliberal global capitalism […] provides the stimulus for both left and right reactions’ [46].

Conclusion

In closing, I would not recommend Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism very highly, principally because the author’s vision of ‘anarcha-Islām’ is exclusive rather than cosmopolitan, in keeping with post-modern, anti-humanist, and sectarian trends emanating from MENA and the West. In his own words, as we have seen, Abdou is a ‘militant jihādi’ [47]. Besides preaching revivalist, neo-orthodox Sunni Islam, he uses a primarily post-colonial perspective to critique settler-colonialism, white supremacy, and Western imperialism. There is no question that these are real ills that must be contested, but the post-colonial framing espoused by Abdou crucially overlooks internal authoritarian social dynamics while facilitating the avowal of the orthodoxies he affirms. This problem also extends to South Asia and its diaspora, as Hindu-nationalist sanghis have taken advantage of the naïveté of many Western progressives to normalize Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s fascist rule [48]. Still, authoritarian rule does not appear to be Abdou’s goal, and his efforts to produce a non-authoritarian vision of Islam are at times noteworthy. A question this review poses is how, in mental and material terms, can adherence to an exclusive doctrine produce an anti-authoritarian world?

Whereas Abdou focuses on challenging and defeating Western hegemony, he avoids mention of the ills propagated by states other than the USA, the European Union, and their allies. Indeed, the disinformation he advances in the conclusion about Assad and Putin’s lack of responsibility for atrocious crimes against humanity in Syria is one with post-colonialists’ downplaying of Russian imperialism, especially in Ukraine. His outright ‘strategic’ support for Assad and lack of sympathy for the women’s protests in Iran, as revealed in the aforementioned podcast interview, typify pseudo-anti-imperialism. Beyond this, the author’s post-anarchist views inform his denial about the expansionism practiced by Islam’s early adherents, and his omissions about the close historical relationship between the new faith and commerce. It is apparent how far his anti-rationalist perspective is from that of the Mutazilites, al-Rawandi, and Ibn Rushd.

The Reality of a Diverse Islam and Diverse Anarchism – Jihad al-Haqq

While Abdou acknowledges the diversity of Islam, this is not reflected in the epistemology he attempts to write. Indeed, like the breadth and width of anarchist beliefs—from anarcha-feminism to egoist anarchism—any weaving together of Islamic belief and anarchism must respect that anarchist beliefs should be able to be built on the many different kinds of Islam that are practiced: Sunnism, Shi’ism, Isma’ilism, and so forth. This is something Abdou should have made clear. The mission of his work was to tie together Islam and anarchism in only one of its possible iterations, in the same way any anarchist proposing a future anarchist society in some theoretical work must concede that such a theoretical work only proposes how one anarchist society might look. This view is correct regardless of anarchist considerations: anthropologically, it is a basic truth that the religions practiced worldwide have many variations (much the same that languages have many variations over certain populations), that are themselves greatly affected by sociological factors, such as socio-economic status, existing power structures within a society, political beliefs, and so on.

Mohamed Abdou did mention this in the last chapter:

‘After all, as the Qur’ān emphasizes: “There is no Coercion in Religion,” and acknowledges: “And had thy Lord willed, all those who are on the earth would have believed all together. Wouldst thou compel people till they become believers?”20 There is no concept of favoritism in Islām. In the Creator’s sight the “best” are the tribes and nations that maintain social justice, egalitarian relations, and ethical and political conduct towards others and nonhuman life. The Qur’ān states: “Not all people are alike”…’

In other places, he reaffirmed the existing diversity of Islamic belief, but did not take it in the direction I hoped.

Ultimately, I fear that because of this precise consideration, Abdou’s project may have been doomed from the start. The synthesis of Islam and anarchism is up to the individual, and such syntheses might go on to become socially popular. Indeed, one of Abdou’s major pillars is that of “ijtihad,” that is, independent reasoning—even if one did not take ijtihad into account, Islam regardless would be diverse politically. The best a work like this can do is to point out anarchistic considerations in developing an interpretation of Islam that is anti-state, anti-capitalist, and so forth; but not establish an anarcha-Islam in its own right. The aim of this work ought to be like a commentary, not a second Qur’an. Nevertheless, it is, in the grand scheme of things, worthy of consideration for both praise and criticism.

Works Cited

Abdou, Mohamed 2022. Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances. London: Pluto.

Achcar, Gilbert 2009. The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Afary, Janet and Kevin B. Anderson 2005. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Ahmad, Aijaz 1998. “Right-Wing Politics, and the Cultures of Cruelty.” Social Scientist, vol. 26, no. 9/10. 3-25.

al-Shami, Leila and Shon Meckfessel 2022. “Why Does the US Far Right Love Bashar al-Assad?” ¡No Pasarán! Ed. Shane Burley. Chico, Calif: AK Press. 192–209.

Asr Anarshism 2022. Forthcoming interview. The Commoner (https://www.thecommoner.org.uk).

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von 2010. West-East Divan. Trans. Martin Bidney. Albany: State University of New York.

Haarman, Ulrich 1978. “Abu Dharr: Muhammad’s Revolutionary Companion.” Muslim World, vol. 68, issue 4. 285–9.

Hammond, Joseph 2013. “Anarchism.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Eds. Gerhard Bowering et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 36–7.

Hensman, Rohini 2018. Indefensible: Democracy, Counterrevolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Kuru, Ahmet T. Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lewinstein, Keith 2013. “Kharijis.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Eds. Gerhard Bowering et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 294–5.

Quran. Trans. Mustafa Khattab. Available online: https://quran.com. Accessed 13 August 2022.

Ramnath, Maia 2022. “The Other Aryan Supremacy.” ¡No Pasarán! Ed. Shane Burley. Chico, CA: AK Press. 210-69.

Rubin, Jared 2013. “Trade and commerce.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Eds. Gerhard Bowering et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 552–4.

Shariati, Ali 2003. Religion vs. Religion. Trans. Laleh Bakhtiar. ABC International Group.

Williams, Wesley 2002. “Aspects of the Creed of Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal: A Study of Anthropomorphism in Early Islamic Discourse.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 34, no. 3. 441–463.

Zaharin, Aisya Aymanee M. 2022. “Reconsidering Homosexual Unification in Islam: A Revisionist Analysis of Post-Colonialism, Constructivism and Essentialism.” Religions 13:702. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080702.

[1] Abdou 115; Quran 2:256, 49:13 (emphasis added).

[2] Abdou 138.

[3] Ibid vii, 14.

[4] Haarman.

[5] Shariati; Kuru 181.

[6] Abdou 10-11, 84; Shariati 26-7.

[7] Abdou 101, 127-46.

[8] Asr Anarshism, forthcoming interview in The Commoner.

[9] Ahmad.

[10] Hensman 119-50.

[11] Abdou 231-2; Hensman.

[12] Hensman.

[13] al-Shami and Meckfessel 198, 208.

[14] Hammond 36.

[15] Kuru 40-2, 48, 103-112, 143-5.

[16] Ibid 216-30.

[17] Abdou 5-8, 32-3, 75, 226.

[18] Ibid 23.

[19] Kuru 25-6; Abdou 168-9, 175, 181.

[20] Abdou 41, 74-5.

[21] Ibid 81.

[22] Ibid 188-220.

[23] Ibid 209 (emphasis in original).

[24] Kuru 17-18, 94-5, 202, 227; Williams 442.

[25] Abdou 17-18.

[26] Lewinstein.

[27] Abdou 207, 228.

[28] Quran 4:59.

[29] Kuru 129; Abdou 149.

[30] Abdou 147-64.

[31] Quoted at Kuru 159.

[32] Kuru 80-1.

[33] Rubin 553.

[34] Ibid 81n86, 200.

[35] Kuru 94.

[36] Abdou 13.

[37] Abdou 47, 123-4, 195.

[38] Ibid 30, 54-5.

[39] Afary and Anderson 50.

[40] Williams 443-8; Zaharin 3, 9.

[41] Goethe 201.

[42] Zaharin 4-8.

[43] Abdou 97, 271n84.

[44] Zaharin 12-17 (emphasis added); Quran 30:21-2.

[45] Abdou 230-2.

[46] Achcar 104–8; Ramnath 244.

[47] Abdou 209 (emphasis in original).

[48] Ramnath.

Tags:Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Abu Hanifa, ahadith, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Ahmet Kuru, Aijaz Ahmad, Aisya Aymanee Zaharin, al-Hariri, anarcha-Islām, anti-capitalism, anti-humanism, Ashari, Asr Anarshism, Averroes, Bashar al-Assad, Brahminism, Buddhism, caste, Christianity, Coffee with Comrades, Da'esh, Daoism, David Duke, Deobandi, Donald Trump, essentialism, Fernand Braudel, Free Syrian Army, fundamentalism, Ghazali, Goethe, Hafez, Hakim Bey, heteronationalism, Hinduism, Ibn al-Rawandi, Ibn Rushd, Imam Shamil, imperialism, Iran, Islam, Islam and Anarchism, Islamic Republic of Iran, Janet Afary, Jesus, Judaism, Kevin Anderson, Kharijites, Khomeinism, Kremlin, Leila al-Shami, Ludwig Feuerbach, Mahdi, Mahsa Amini, Maia Ramnath, Max Stirner, Mikhail Bakunin, Milad Dokhanchi, militarism, Mohamed Abdou, Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdallah, Mutazilites, Nizamuddin Auliya, Organise Magazine, post-anarchism, post-colonialism, post-modernism, Protestantism, Pseudo-Anti-Imperialism, Quran, Quraysh, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Rohini Hensman, Rumi, Russia, Sayyid Qutb, SDF, sectarianism, Shi'ism, Shon Meckfessel, Sikhism, Sufism, Sunnism, Syria, Taftazani, Tamim al-Barghouti, tankies, TEV-DEM, tikkun olam, Ukraine, ulema-State alliance, Vladimir Putin, YPG

Posted in 'development', Abya Yala, anarchism, book reviews, displacement, Egypt, Europe, fascism/antifa, health, imperialism, Iran, Kurdistan, literature, Revolution, U.S., Ukraine, war | Leave a Comment »