Check out my recent conversation on Thomas Wilson Jardine’s podcast Ideologica Obscura about my review of Mohamed Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism on The Commoner:

Posts Tagged ‘Saudi Arabia’

Conversation on Modern Islamic Anarchism

September 21, 2023Tags:Afghanistan, Ahmet Kuru, anarcha-Islām, anarchism, Bashar al-Assad, Circassians, current events, Gilbert Achcar, history, Ideological Obscura, Iran, Islam, itjihad, Mahsa Amini, Modern Islamic Anarchism, Mohamed Abdou, NATO, Pseudo-Anti-Imperialism, Qatar, Russia, Salafism, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Taliban, Thomas Wilson Jardine, Ukraine

Posted in 'development', Afghanistan, Algeria, anarchism, audio, book reviews, China, displacement, Egypt, Europe, fascism/antifa, history, imperialism, Iran, literature, Revolution, Syria, U.S., Ukraine, war | Leave a Comment »

Islamic Anti-Authoritarianism against the Ulema-State Alliance

April 5, 2023Abbas al-Musavi, The Battle of Karbala

The second part in a series on Islam, humanism, and anarchism. This review includes an alternate perspective by Jihad al-Haqq.

First published on The Commoner, 5 April 2023. Shared using Creative Commons license. Feel free to support The Commoner via their Patreon here

Building on my critical review of Mohamed Abdou’s Islam and Anarchism (2022), this article will focus on Ahmet T. Kuru’s Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment (2019). Here, I will concentrate on Kuru’s study of Islam, history, and politics, focusing on the scholar’s presentation of the anti-authoritarianism of the early Muslim world, and contemplating the origins and ongoing oppressiveness of the alliance between ulema (religious scholars) and State in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). I will examine Kuru’s analysis of the “decline thesis” about the intellectual, economic, and political counter-revolutions that led Muslim society to become dominated by military and clerical elites toward the end of the Golden Age (c. 700–1300); briefly evaluate the author’s critique of post-colonial theory; and contemplate an anarcho-communist alternative to Kuru’s proposed liberal strategy, before concluding.

Perhaps ironically, Kuru may uncover more Islamic anti-authoritarianism than Abdou does in Islam and Anarchism. Marshaling numerous sources, Kuru clarifies that a degree of separation between religion and the State existed in Islam’s early period; that ‘Islam emphasizes the community, not the state’; and that ‘the history of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates was full of rebellions and oppression.’ In fact, the Umayyad dynasty, which followed the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661) that itself had succeeded the Prophet Muhammad after his death, generally lacked religious legitimation, given that its founders persecuted the Prophet’s family during the period known as the Second Fitna (680–692) [1]. Such sadism was especially evident at the momentous battle of Karbala (680), at the conclusion of which the victorious Umayyad Caliph Yazid I murdered the Imam Hussein ibn Ali, grandson of the Prophet and son of the Rashidun Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib, together with most of his relatives [2]. Shi’ites mourn these killings of Hussein and his family during the month of Muharram, considered the second-holiest month of the Islamic calendar after Ramadan. Currently being observed by Muslims across the globe, Ramadan marks the first revelation of the Quran to Muhammad in Jabal al-Nour (‘the mountain of light’) in the year 610. (For an artistic representation of the latter event, see the featured painting from the Hamla-yi Haidari manuscript below.)

Politically speaking, early Muslims rejected despotism and majesty and emphasized the importance of the rule of law, such that ‘traditional Muslim[s were] suspicio[us] of Umayyad kingship’ [3]. Following the Mutazilites, the Iranian revolutionary Ali Shariati claimed the fatalist belief in ‘pre-determination,’ which was encouraged by the orthodox theologian Ashari, to have been ‘brought into being by the Umayyids’ [4]. Along similar lines, in the Quran it is written, ‘if one [group of believers] transgresses against the other, then fight against the transgressing group,’ while one of the Prophet Muhammad’s ahadith (sayings) declares that the “best jihad is to speak the truth before a tyrannical ruler’[5]. During the time of Muhammad and the Rashidun Caliphs, hence, Islamic politics were rather progressive, for the nascent faith’s founders rejected both oppressive authority, whether exercised locally in Arabia or afar in the Byzantine Empire, and the injustice of the Brahmin caste system. In this vein, all founders of the four Sunni schools of law (fiqh), and some early Shi’ite imams, refused to serve the State. In retaliation, they were persecuted, imprisoned, and even killed [6].

During the Abbasid Caliphate, radical freethinkers such as the physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 854–925) and Ibn Sina (980–1037) made breakthroughs in medical science, while the polymath Biruni (973–1048) advanced the field of astronomy, just as al-Razi and Biruni respectively criticized religion and imagined other planets. Mariam al-Astrulabi (950–?) invented the first complex astrolabe, which had important astronomical, navigational, and time-keeping applications. Plus, Baghdad’s House of Wisdom boasted a vast collection of translations of scholarly volumes into Arabic, and a number of hospitals were founded in MENA during the Abbasid and Mamluk dynasties. Farabi (c. 878–950) emphasized the philosophical importance of happiness, Ibn Bajja (c. 1095–1138) likewise stressed the centrality of contemplation, and Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) made critical contributions to sociology through his insights into asabiyya, or group cohesion. Perceptively, Ibn Khaldun declared that the ‘decisions of the ruler […] deviate from what is right,’ while concurring with some of the most radical Kharijites in holding that the people would have no need for an imam, were they observant Muslims [7].

At the same time, Kuru explains that Islam’s Golden Age (c. 700–1300)—which allowed for the birth of a freer scholarly, political, and commercial atmosphere in the Muslim world, relative to Western Europe—was driven by a ‘bourgeois revolution’ of mercantile capitalism, to which Islam itself contributed [8]. With their private property and contracts ensured, as stipulated by the Quran and Prophet Muhammad’s Medina Charter (622–624), Muslim merchants could accumulate the capital with which to maintain financial, political, and intellectual independence from the State. Indeed, in contrast to the clerics who have served the authorities since the medieval congealing of the ulema-State, most Islamic scholars from this period worked in commerce, thus making possible their patronage of creative thinkers and scientists [9]. While the dynamism of dar al-Islam (the world’s Muslim regions)produced renowned intellectuals like al-Rawandi, al-Razi, Farabi, al-Ma’arri, Ibn Sina, Ibn Khaldun, and Ibn Rushd, among others, freethinking in the West was simultaneously stifled by religious and military elites. In this light, Kuru insightfully compares Islam’s Golden Age to the subsequent European Renaissance, whose coming was indeed facilitated by scholarship from and trade with the Muslim world [10].

The Decline Thesis, and an Anarchist Alternative

Soon enough, however, the ‘[p]rogressive atmospheres’ created by Islam would yield to reaction [11]. With the proclamation in 1089 of a decree by the Abbasid Caliph Qadir outlining a strict Sunni orthodoxy that would exclude Mutazilites, Shi’ites, Sufis, and philosophers, the ulema-State alliance was forged. This joint enterprise created a stifling and stagnating bureaucratic atmosphere opposed to progress of all kinds. Internally, this shift was aided by the eclipse of commerce by conquest, looting, and the iqta system—a feudal mechanism whereby the State distributed lands to military lords and in turn expanded itself through taxes extracted from peasant labor. Additionally, the eleventh-century founding of Nizamiyya madrasas, which propagated Ashari fatalism and stressed memorization and authority-based learning, was decisive for this transformation. Externally, the violence and plundering carried out by Crusaders and Mongols against the Muslim world led to further marginalization of scholars and merchants on the one hand, and deeper legitimization of military and clerical elites on the other [12].

Through comparison, Kuru contemplates how this joint domination by ulema and State—characterized by bureaucratic despotism, State monopolies, and intellectual stagnation—mimics the backwardness of Europe’s feudal societies during the Dark and Middle Ages. Still, just as anti-intellectualism, clerical hegemony, and political authoritarianism are not inherent to Judaism, Christianity, or Western society, this reactionary partnership is not innate to Islam either, considering the remarkable scientific, mathematical, and medical progress made during Islam’s early period. Only later did the combination of Ghazali’s sectarianism, Ibn Taymiyya’s statist apologism, and the Shafi jurist Mawardi’s centralism result in the consolidation of Sunni orthodoxy and despotic rule. Indeed, Kuru traces the germ of this noxious ulema-State alliance to the political culture of the Persian Sasanian Empire (224–651), which prescribed joint rule by the clerics and authorities. In this sense, the ‘decline thesis’ about the fate of scholarship and freethinking in Muslim society cannot be explained by essentialist views that define Islam by its most reactionary and anti-intellectual forms [13].

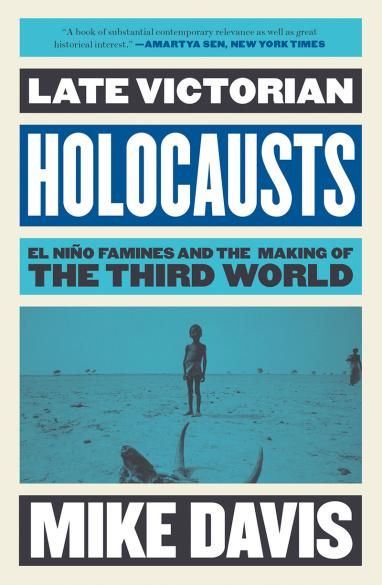

More controversially, Kuru equally concludes that the violence, authoritarianism, and underdevelopment seen at present in many Muslim-majority countries cannot be explained solely by either post-colonial theory or a primary focus on Western (neo)colonialism. This is because post-colonial writers, like Islamists, discourage a critical analysis of the “ideologies, class relations, and economic conditions” of Muslim societies, leading them to overlook, and thus fail to challenge, the enduring presence of the ulema-State alliance [14]. In parallel, the caste system persists in post-colonial India, while “British and German scholars did not invent caste oppression,” as much as fascists across the globe have been inspired by it [15]. At the same time, according to the late Marxist scholar Mike Davis, European imperialism, combined with excess dryness and heat from the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon, led to famines that killed between 30 and 60 million Africans, South Asians, Chinese, and Brazilians in the late nineteenth century. The Indian economist Utsa Patnaik estimates that British imperialism looted nearly $45 trillion from India between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries.

Currently, bureaucratic authoritarianism in MENA is financed by the mass-exploitation of fossil fuels, which finances the State’s repressive apparatus, hinders the independence of the workers and the bourgeoisie, and disincentivizes transitions to democracy [16]. Certainly, the West, which runs mostly on fossil fuels, and whose leaders collaborate with regional autocrats, is complicit with such oppression, whether we consider its long-standing support for the Saud dynasty (including President Biden’s legal shielding of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman against accountability for his murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi), more recent ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the past alliance with the Pahlavi Shahs, or the love-hate relationships with Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi. The US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, launched twenty years ago, killed and displaced similar numbers of people as Assad and Putin’s counter-revolution has over the past twelve years.

Overall, Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment helps illuminate the religious, political, and economic dimensions of the legacy of the authoritarian State in MENA. Moving forward, Kuru’s proposed remedy to the interrelated and ongoing problems of authoritarianism and underdevelopment in Muslim-majority countries is political and economic liberalisation. The author makes such liberal prescriptions based on his historical analysis of the progressive nature of the bourgeoisie, especially as seen during the Golden Age of Islam and the European Renaissance. As an alternative, he mentions the possibility that the working classes could help democratize the Muslim world, but notes that they are not an organized force [17]. Moreover, in a 2021 report, ‘The Ulema-State Alliance,’ Kuru clarifies that he is no proponent of ‘stateless anarchy,’ as might be pursued by anarcho-syndicalist or anarcho-communist strategies.

Yet, it is clear that empowering the bourgeoisie has its dangers: above all, global warming provides an especially stark reminder of the externalities, or ‘side-effects,’ of capitalism. Plus, at its most basic level, the owner’s accumulation of wealth depends on the rate of exploitation of the workers, who cannot refrain from alienated labor, out of fear of economic ruin for themselves and their loved ones. This is the horrid treadmill of production. As the critical theorist Herbert Marcuse recognized, capitalism is an inherently authoritarian, hierarchical system [18]. Although bourgeois rule may well allow for greater scientific, technical, and scholarly progress than feudal domination by clerical-military elites, whether in Europe, MENA, or beyond, the yields from potential advances in these fields could be considerably greater in a post-capitalist future. Science, ecology, and human health could benefit tremendously from the communization of knowledge, the overcoming of fossil fuels and economic growth, the abolition of patents and so-called ‘intellectual property rights,’ the socialization of work, and the creation of a global cooperative commonwealth. Considering how Western and Middle Eastern authorities conspire to eternally delay action on cutting carbon emissions as climate breakdown worsens, both Western and MENA societies would gain a great deal from anti-authoritarian socio-ecological transformation.

In sum, then, I reject both the ulema-State alliance and Kuru’s suggested alternative of capitalist hegemony—just as, in mid-nineteenth-century Imperial Russia, the anarchists Alexander Herzen and Mikhail Bakunin rebuked their colleague Vissarion Belinsky’s late turn from wielding utopian socialism against Tsarism to espousing the view that bourgeois leadership was necessary for Russia [19]. In our world, in the near future, regional and global alternatives to bourgeois-bureaucratic domination could be based in working-class and communal self-organization and self-management projects, running on wind, water, and solar energy. Such experiments would be made possible by the collective unionization of the world economy, and/or the creation of exilic, autonomous geographical zones. Despite the “utopian” nature of such ideas, in light of the profound obstacles inhibiting their realization, this would be a new Golden Age or Enlightenment of scientific and historical progress, whereby a conscious humanity neutralized the dangers of self-destruction through raging pandemics, global warming, genocide, and nuclear war.

Conclusion: For Anarcho-Communism

In closing, I express my dynamic appreciation for Kuru’s Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment, which aptly contests both essentialist and post-colonialist explanations for the violence, anti-intellectualism, and autocratic rule seen today in many Muslim-majority societies. Kuru highlights the noxious work of the ulema-State alliance to impose Sunni and Shi’i orthodoxies; legitimize the authority of the despotic State; and reject scientific, technological, social, and economic progress. Keeping in mind the anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker’s framing of anarchism as the “confluence” of socialism and liberalism, I welcome the author’s anti-authoritarian proposals to revisit the freethinking of the Golden Age of Islam and liberalise the Muslim world, but contest Kuru’s apparent pro-capitalist orientation. In this vein, the writer’s recommendations could be radicalized to converge with the “Idea” of a global anarcho-communist movement that rejects clerical and political hierarchies as well as capitalism, militarism, and patriarchy, in favor of degrowth, a worldwide commons, international solidarity, mutual aid, and working-class and communal self-management of economy and society.

Western Colonialism and Imperialism – Jihad al-Haqq

Whilst Kuru’s historical description of the ulema-state alliance usefully describes the historical oppressions of Muslim-majority nations, it does not explain their continued existence. Especially not in the face of the Arab Spring and, as Kuru himself cites, the vast popularity of democracy amongst Muslims (page xvi, preface). Indeed, a name search reveals that the term ‘Arab Spring’ is used only four times throughout the entire book—three of those times are in the citations section. It is stunning to have a book talking about Islam, authoritarianism, and democracy, without mentioning the momentous event of the Arab Spring. That is, the concept of the ‘ulema-state alliance’ is useful in describing the internal form of social oppression in Muslim-majority societies, but it does not explain why and how those forms continue to exist, which is primarily due to Western imperialism.

Ahmet Kuru’s discussion regarding the ulema-state alliance seems geared towards explaining the question of why Muslim-majority countries are less peaceful, less democratic, and less developed. The question is primarily a political-economic question, not a question of faith, and thus requires a political-economic answer, which he acknowledges. However, he contends that Western colonialism is not a primary material cause for the unrest and destitution in Muslim majority nations; rather, it is the ulema-state alliance. This is a strange argument, for several reasons.

Firstly, his criticism of postcolonial writers is a strawman. The main hypothesis of postcolonial writers is that oppression in Muslim majority nations, whatever form it takes (including the ulema-state alliance), is primarily financed and armed by Western powers and Gulf nations; it is to explain the prevention of democracy in Muslim-majority nations.

He writes:

‘The anti-colonial approach has some power in explaining the problem of violence in certain Muslim countries. But Western colonization/occupation is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for violence. It is not sufficient, as there have been non-Muslim and Muslim countries that were colonized or occupied but where many influential agents did not choose to use violence. Such leading figures as Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–98) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), for example, adopted a position of non-violence against British colonization in India. Western colonization/occupation is not a necessary condition either, because several non-Western countries and groups have fought each other for various reasons. The long list includes the Iran-Iraq War and recent civil wars in several Arab countries. In Turkey, violence has continued between the Turkish state and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) for more than three decades, regardless of whether Turkey was ruled by secularists or Islamists, and regardless of whether the PKK defended or renounced Marxist-Leninist ideology.’

He says that Western colonization and occupation is not a sufficient condition for the violence in Muslim-majority countries, since other countries under the same conditions did not choose to use violence. However, this flies in the face of the history of decolonial movements, since many other countries other than the Muslim-majority ones did choose violence as a method, while several Muslim-majority thinkers did and do advocate non-violence. Decolonization as a process in each country cannot be easily separated into a non-violent and violent category, such as in Indian decolonization being entirely non-violent and decolonization in Algeria being entirely violent, as you will find both non-violent and violent currents in each country advocating decolonization. Moreover, whether a decolonial process is more violent or not overwhelmingly depends on other socio-political factors: the British did not let go of India because they suddenly found enlightenment about the wrongdoing of their ways, and it would be difficult to say that Indian decolonization would not have turned more violent if the British had not ended up letting go of the Raj. We must also question the assumption that colonialism ended at all: there have been many convincing works that effectively argue that instead of colonisation ending, we have simply moved to another form of colonisation facilitated through nation states, rather than overt conquest. Parts of these works make very hard to dismiss cases, backed up by historical records, that show that much of the violence that exists in Global South countries, including Muslim-majority ones, is not due to internal cultural or social institutions, but due to the financing and arming of violent forces in the country. The existence of destitution can be directly linked to such Western-supported authoritarians in these societies.

The United States, for example, armed and supported the dictator Suharto in Indonesia, who is one of the worst mass murderers of the 20th century, against the popular Communist Party in Indonesia. The US is also one of Saudi Arabia’s greatest allies, with Saudi Arabia likely having the most institutionalized form of the ulema-state alliance. William Blum’s classic Killing Hope goes through many details of the various democracy movements throughout the world which the United States has crushed, including in Muslim-majority nations. Perhaps amazingly, the list of examples Kuru uses to support the argument that Western imperialism cannot be stated to be a necessary condition of violence do indeed have a traceable Western influence. Furthermore, the phenomenon of imperialism, which is separate from colonialism and the main focus of many postcolonial writers, does not seem to factor into his analysis.

Moreover, violence as a response to colonisation is almost a universal given—it is not the expression of culture anymore than a person being attacked and choosing to fight back is an expression of ideology. Revolutionary violence is a response to violence: the colonised are forced to be violent in response to the violence waged upon them, regardless of what culture they have, and all people have the right to violence for self-defense. For that, I do not think a detailed discussion is required.

The thesis which Kuru is attempting to argue here is that both revolutionary violence and internal violent structures are expressions of the same structures within Muslim-majority nations that cause more violence to happen. I do not believe this conclusion is tenable, since, on the one hand, revolutionary violence is waged defensively in response to colonialism, and on the other, the internal violence of current Muslim-majority nations do have a traceable Western influence: it would be difficult to argue that Iraq today would be as violent as it is if the United States had not diplomatically and militarily supported the rise of Saddam Hussein, and had not invaded Iraq in 2003. Both of these sorts of violence do not have the same social, political, and economic roots, and therefore cannot be classed as expressions of the same socio-cultural phenomenon.

Kuru’s answer to the continued existence of oppression in the Middle East is economic and political liberalisation; however, as demonstrated with the Arab Spring, the idea of political liberalisation will not be tolerated by the various monarchies and dictatorships of the Middle East, who are largely supported and armed by the United States. Furthermore, Kuru’s proposal of political and economic liberalisation is not really liberalisation—at the very least, not liberalisation if we understand “liberalisation” to mean liberating. He proposes the introduction of a new class of economic capitalist elites, which is hardly an improvement from the ulema-state alliance—never mind that Middle Eastern nations are already economically liberalised. While Kuru’s text is useful in discussing the form of historical oppressions, it reaches too far in its concluding theory regarding the continued existence of despotism in the Middle East.

Works Cited

Abdou, Mohamed 2022. Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances. London: Pluto.

Afary, Janet and Kevin B. Anderson 2005. Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Hammond, Joseph 2013. “Anarchism.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Eds. Gerhard Bowering et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 36–7.

Kuru, Ahmet T. 2019. Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Malia, Martin 1961. Alexander Herzen and the Birth of Russian Socialism. New York: Universal Library.

Marcuse, Herbert 1968. Negations: Essays in Critical Theory. Boston: Beacon Press.

Quran. Trans. Mustafa Khattab. Available online: https://quran.com. Accessed 13 August 2022.

Ramnath, Maia 2022. “The Other Aryan Supremacy.” ¡No Pasarán! Ed. Shane Burley. Chico, CA: AK Press. 210-69.

Shariati, Ali 2003. Religion vs. Religion. Trans. Laleh Bakhtiar. ABC International Group.

References

[1] Kuru 10-12, 71.

[2] Afary and Anderson.

[3] Kuru 89.

[4] Shariati 32; Kuru 95.

[5] Quran 49:9 (emphasis added); Abdou 201.

[6] Kuru 70-2, 88-9.

[7] Ibid 76-80, 131-2, 134, 139-41, 150; Hammond 36.

[8] Kuru 83-87.

[9] Quran 4:29; Abdou 116; Kuru 73.

[10] Kuru 93, 159-61.

[11] Ibid 116-7.

[12] Ibid 96-102, 126-7.

[13] Ibid xvi-xv, 96-7, 112-16, 146-7, 185-203, 227-235.

[14] Ibid 34, 234.

[15] Ramnath 254.

[16] Kuru 49-53.

[17] Ibid 55n107.

[18] Marcuse 9-11, 18-19.

[19] Malia 353-6.

Tags:Abbasid dynasty, Ahmet Kuru, Ahmet T. Kuru, al-Ma'ari, al-Rawandi, al-Razi, Alexander Herzen, Ali Shariati, anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, ancom, Ashari, authoritarianism, Biruni, Brahminism, Byzantines, capitalism, caste system, decolonization, democracy, Enlightenment, ENSO, Farabi, fiqh, Ghazali, global warming, House of Wisdom, Ibn Bajja, Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Sina, Ibn Taymiyya, Indonesia, Islam, Islamic Golden Age, Islamism, Jabal al-Nour, Javier Sethness, Jihad al-Haqq, Kharijites, Killing Hope, Late Victorian Holocausts, Liberalism, Mamluk dynasty, Mariam al-Astrulabi, Mawardi, Medina Charter, MENA, Mike Davis, Mikhail Bakunin, Muammar Qaddafi, Muharram, Mutazila, Mutazilites, Nizamiyya, PKK, post-colonialism, Prophet Muhammad, Qadir, Ramadan, Rashidun, Renaissance, Rudolf Rocker, Saddam Hussein, Samarkand, Saudi Arabia, Shi'ism, socialism, Sufism, UAE, ulema-State alliance, Umayyad, Umayyad dynasty, Utsa Patnaik, Vasily Vereshchagin, Vissarion Belinsky, WWS

Posted in 'development', Abya Yala, anarchism, book reviews, China, climate catastrophe, displacement, ecology, health, imperialism, Iran, Iraq, Kurdistan, literature, Palestine, reformism, Revolution, Russia/Former Soviet Union, South Asia, Syria, U.S., war | 1 Comment »

What Were Stalin’s Real Crimes? Critique of “A Marxist-Leninist Perspective” on Stalin (Part II/III)

November 15, 2018

The meaning of forced collectivization: an irrigation project in Fergana, Eastern Kazakhstan, 1935 (courtesy David Goldfrank)

“It is in the nature of ideological politics […] that the real content of the ideology […] which originally had brought about the ‘idea’ […] is devoured by the logic with which the ‘idea’ is carried out.”

– Hannah Arendt1

What’s the biggest problem with the “criticisms” of Stalin raised by the “Proles of the Round Table”? That they are so disingenuous and anemic. One of the three critiques raised—about Spain—in fact isn’t critical of Stalin, while we’ve seen (in part I) how the “criticism” on deportations is entirely misleading. A related question might be to ask how it looks for two presumably white U.S. Americans to criticize Stalin for some (1-2%) of his deportations of ethnic Germans, but not to do so when it comes to the dictator’s mass-deportations of Muslims, Buddhists, and other indigenous peoples. At least Mao Zedong judged Stalin as being “30 percent wrong and 70 percent right.”2 For Jeremy and Justin, though, Stalin appears to have been at least 90%, if not 95%, right. Maybe we can soon expect the “Proles of the Round Table” Patreon to begin selling wearables proclaiming that “Stalin did nothing wrong.”

Besides the aforementioned Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the May Days, and the mass-deportations of ethnic minorities, let’s now consider five of Stalin’s real crimes.

1. “Socialism in One Country”: Stalinist Ideology

His revision, together with fellow Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin, of the tradition of socialist internationalism to the reactionary, ultra-nationalist idea of “socialism in one country.” Stalin and Bukharin arrived at this conclusion to compete against Lev Trotsky’s rival concept of “permanent revolution,” which calls first for a European and then global federation of socialist republics. This Stalinist doctrine, which demanded that the interests of the Soviet bureaucracy be considered first within the Third International (or Comintern), can explain both the General Secretary’s demand to crush the anarchists in Spain in 1937 and his effective facilitation of Hitler’s rise to power by means of the disastrous Comintern policy that considered the social-democratic (that is, non-Stalinist) opposition to Hitler to be “social-fascist.” The General Secretary would only reverse course and endorse a “Popular Front” strategy after Hitler had taken power.3 Stalinist ultra-nationalism finds contemporary purchase among neo-fascist, national-Bolshevik movements, whereas—perhaps ironically—the Comintern doctrine on “social fascism” has echoes today among ultra-leftists disdainful of coalition-building with more moderate political forces (e.g., as in the 2016 U.S. presidential election). Moreover, Stalin’s preference for “socialism in one country” can help us understand the Soviet Union’s continued sale of petroleum to Mussolini following this fascist’s military invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935.4 Within this same vein, and anticipating the affinity of today’s neo-Stalinists for campist “analyses” of international relations, Moscow variously supported the feudalist Guo Min Dang (GMD) in China, the Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Iranian Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the Afghan King Amanullah Khan, and Ibn al-Sa’ud (founder of Saudi Arabia) during this time on the grounds that these leaders staunchly opposed the West, despite their great distance from any kind of socialist paradigm.5

Courtesy Voline, The Unknown Revolution

2. Stalinist Imperialism

His “Great-Russian” chauvinism, as manifested in his brutally imperialist policies toward ethnic minorities—particularly the deportations of Muslims (as mentioned above in part I)—and other subject-peoples of the former Tsarist empire, whose colonial project Stalin enthusiastically embraced. Though Georgian by origin (his birth name was Ioseb Jughashvili), Stalin (whose Russian nom de guerre means “man of steel”) was “the most ‘Russian’ of the early leaders” who advanced not only “socialism in one country,’ but […] a socialism built on a predominantly Russian foundation.”6 According to Dunayevskaya, Stalin’s “national arrogance” was “as rabid as that of any Tsarist official.”7 In contrast to his mentor and supervisor Vladimir I. Lenin, who at least formally supported the right of self-determination for the oppressed nationalities of the Tsarist empire while greatly violating this principle in practice, Stalin was openly imperialist on the national question: according to the terms of this relationship, the colonies were to be “plundered for raw materials and food to serve the industrialisation of Russia.”8 It therefore remains clear that, under the Soviet Union, “Russia was not a nation state but an empire, an ideological state. Any definition as a nation-state would probably have excluded at least the non-Slavs, and certainly the Muslims.”9 Accordingly, the official history taught in Stalin’s USSR rehabilitated the mythical Tsarist narrative that the Russian “Empire had brought progress and civilisation to backward peoples.”10

Ethnographic map of the former Soviet Union. Date unknown

In Georgia, a former Tsarist-era colony located in the Caucasus Mountains, the social-democratic Menshevik Party declared independence in 1918 to found the Georgian Democratic Republic, otherwise known as the Georgian Commune, wherein parliamentary democracy and a relatively collaborative relationship among the peasantry, proletariat, and political leadership lasted for three years, until Stalin and his fellow Georgian Bolshevik Sergo Ordzhonikidze organized a Red Army invasion in 1921 which crushed this courageous experiment in democratic socialism. The errant ex-colony of Georgia was thus forcibly reincorporated into the ex-Tsarist Empire—by then, the “Transcaucasian Federated Soviet Republic,” part of the Soviet Union.11 Besides Georgia, this “Transcaucasian Federated Soviet Republic” would include Azerbaijan and Armenia, which had also been occupied by the Red Army in 1920.12

In the Muslim-majority provinces of Central Asia, otherwise known as Turkestan, the poorest region of the former Tsarist Empire, Lenin and Stalin sided with the interests of the Russian settlers against the Muslim peasantry.13 In Orientalist fashion, the Bolsheviks considered Central Asia’s “Muslims as culturally backward, not really suitable to be communists and needing to be kept under a kind of tutelage.”14 Yet in light of the sustained Basmachi revolt waged by Muslim guerrillas against Soviet imperialism in the first decade after October 1917, Stalin also recognized the significant threat these colonized Muslims could pose to the Soviet Union—hence his active discouragement of pan-Islamism and pan-Turkism by means of cutting off the USSR’s Muslims “subjects,” many of them ethnically and linguistically Turkic, from the rest of the Ummah (Islamic global brotherhood or community) abroad. An early 1930’s law punishing unauthorized exit from the USSR made observation of hajj, or the pilgrimage to Mecca, quite impossible.15 The expulsion from the Communist Party (1923) and subsequent imprisonment (1928) of the Volga Tatar Sultan Galiev, a pan-Islamist “national-communist” who envisioned organizing the Turkic Muslims into a fighting force against Western imperialism, followed a similar logic.16

In the Stalinist conception, the numerous subject-peoples of the Soviet Union could be classified hierarchically according to their “stage of development,” as based on their mode of production and whether or not they had a written language, such that supposedly more ‘advanced’ peoples would qualify as ‘nations’ that were granted the status of “Soviet Socialist Republic” (SSR), whereas “less developed” peoples would be granted “Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics” (ASSR), while those without written languages would be placed in “Autonomous Regions” (AR), or “National Territories” (NT). In 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, there existed 14 SSR’s, 20 ASSR’s, 8 AR’s, and 10 NT’s in the USSR.17

Map of Soviet administrative subdivisions, 1989. Notice the numerous ASSR subdivisions in Central Asia

This systematic atomization of oppressed nationalities followed Stalin’s “principle of the dual bridgehead,” whereby the State would favor those minorities that could assist the USSR in expanding its reach while repressing other minorities whose existence could serve as a “fifth column” for the USSR’s rivals. In part I of this critique, we saw how this rationale played out in Stalin’s mass-deportations: the General Secretary felt justified in forcibly transferring the Turkic Muslim Meskhetian people, among others, because they were supposedly too close to the Turkish State headed by Kemal Atatürk. Furthermore, this principle can be gleaned in the Soviet Communist Party’s initial favoring of Uzbeks over Tajiks beginning in 1924, followed by a 180° shift in perspective upon the overthrow of Afghanistan’s King Amanullah (a Pashtun) by Bacha-i Saqqao, a Tajik, in 1928—leading to the proclamation of the Tajikistan SSR in 1929.18 The capital city of Dushanbe was subsequently renamed as “Stalinabad.”19 In addition, whereas the Communist Party favored its own Kurdish minority, some of whom included refugees, because it could use them in the future as pawns against Iran and Turkey, it had refused to support Kurdish and Turkmen rebellions abroad against Turkey and Iran in 1925. Above all, Stalin’s nationalities policy achieved its greatest “success” in its complex partition of Turkestan by means of the drawing-up of borders that were defined along ethno-nationalist lines: just look at the region’s current borders (see map above), which are based on those concluded by Stalin’s regime. In thus pitting Central Asia’s mosaic of different ethno-linguistic groups against each other, Stalin definitively laid the pan-Islamist specter to rest.20 Dunayevskaya’s observation here seems apt: it was in Stalin’s “attitude to the many [oppressed] nationalities” that the General Secretary’s “passion for bossing came out in full bloom.”21

A Soviet mosaic in Karaghandy, Kazakhstan (Courtesy The Guardian)

Stalin’s imperialist assertion of power over Central Asia, which imposed the collectivization of cattle herds and the nationalization of bazaars and caravans managed by indigenous peoples while promoting Russian settlements, resulted in famine and revolt.22 It involved a high-modernist assault on Islam in the name of emancipating women and remaking traditional patriarchal Turkic social relations, as we shall examine in more detail in the third part of this response.

Regarding Ukraine, see the section on Jeremy and Justin’s Holodomor denial in the third part of this response. Briefly, Jeremy’s Russian-chauvinist attitude toward all matters Ukrainian comes through at a fundamental linguistical level when he refers to Ukraine as “the Ukraine.” This formulation, like the Russian «на Украине» (“in the Ukraine”), is an imperialist way of referring to the country, which is not just a colony of Russia or the Soviet Union (as in, “the Ukrain[ian province]”). The proper way is to refer just to Ukraine, as in the Russian equivalent «в Украине» (“in Ukraine”).

Such attitudes are shared by Ó Séaghdha, who falsely claims Ukraine today to be a “bastion of the far right and neo-Nazism,” just as Justin compares “Ukrainian nationalists” to the U.S.-based Proud Boys. One’s mind is boggled: as of July 2018, the ultra-nationalist Svoboda Party had only 6 seats, or 1.3%, in Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada, while in both rounds of elections held in 2014, Svoboda and Right Sector alike gained less than 5% of the vote.23 In fact, Ukraine has held its first major LGBT Pride marches following the Euromaidan protests which overthrew the Putin-affiliated President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. Meanwhile, by focusing on the supposedly ‘fascist’ Ukrainians,24 Ó Séaghdha and his guests deny the global reach of Putin’s neo-Nazism, from his 2014 occupation of Crimea and invasion of Eastern Ukraine and his subsequent mass-detention of Crimean Tatar Muslims, including in psychiatric hospitals, to his regime’s criminalization of homosexuality, decriminalization of domestic violence, and genocidal intervention in support of the Assad Regime in Syria—to say nothing of his mutual affinities for the Trump Regime. How ironic is this misrepresentation, then, considering that Ukraine was the “centerpiece of Hitler’s vision of Lebensraum.”25

A typically socialist-realist depiction of a collective farm celebration, by Arkady Plastov (1937): presumably, this is how neo-Stalinists and ‘Marxist-Leninists’ idealize the outcomes of forcible collectivization in the Soviet Union.

3. Stalinist State-Capitalism

His advocacy and implementation of state capitalism in the Soviet Union, whereby the basic relationship of exploitation between capital and labor persisted after the Russian Revolution, with the difference that capital in this case was managed and expanded by the Communist Party bureaucracy rather than the private capitalist class.26 Upheld by the Army and police, the Soviet economy reduced workers to mere slaves: during the existence of the USSR, workers could not regulate, choose, or control their overseers and administrators, much less anticipate not having any, as through anarcho-syndicalist organization, or autogestion (самоуправление). In the USSR,

“[t]he State [wa]s [the worker’s] only employer. Instead of having thousands of ‘choices,’ as is the case in the nations where private capitalism prevails, in the U.S.S.R. (the U.S.C.R. [Union of State-Capitalist Republics: Voline]) the worker ha[d] only one. Any change of employer [wa]s impossible there.”27

Following the Revolution, “[f]or the Russian workers, […] nothing had changed; they were merely faced by another set of bosses, politicians and indoctrinators.”28

Peasants under Stalin were similarly reduced to serfs, particularly during and following the forced collectivization process that began in 1928. Continuing with the precedent of the Bolshevik policy of “War Communism,” which had involved considerable extraction of grain and the conscription of young men from the peasantry, Stalin declared war on the countryside, expropriating all lands held by these peasants and concentrating these into kolkhozi, or “collective possessions,” and sovkhozi, or State farms, which were to be worked by the peasants in the interests of the State.29 This nationalization did not discriminate between “rich” peasant, or kulak, and poor—in contrast to the misleading presentation Jeremy and Justin make of Stalin’s forcible collectivization campaign. The “Proles of the Round Table” deceptively explain the emergence of the “kulaks” by referring to the Tsarist Interior Minister Peter Stolypin’s land reforms of 1906, while saying nothing about Lenin’s “New Economic Policy” of 1921, which formally reintroduced private property. They also completely misrepresent Stalin’s collectivization policy, which proceeded at the points of bayonets, as a natural outgrowth of the traditional peasant commune (mir or obshchina), which had resisted the Tsarist State for centuries. In fact, it was arguably through Stalinist forcible collectivization that the Russian countryside fell under the control for the first time.30 As peasant resistance to this “total reordering of a rural civilization from the top down” mounted, including an estimated 13,000 “mass disturbances” just in 1930, Stalin’s regime resorted to atrocious counter-insurgent tactics to bring the countryside to heel, including mass-executions, reprisals, and the resulting famines of 1931-1933 in Ukraine, South Russia, and Kazakhstan.31 The Stalinist regime conveniently expanded the definition of exactly who was a “kulak” from a class-based to a political definition, such that even poor peasants who opposed forcible collectivization could be labeled “kulaks” and deported to Siberia, the Far North, and Central Asia, as about 1.8 million peasants were in 1930-1931. As during the numerous other episodes of mass-deportations devised by Stalin, mortality rates among “dekulakized” peasants were high.32

Puzzlingly, the “Proles of the Round Table” claim this collectivization to have been “extremely successful” in providing “stability” by the mid-1930’s, the resistance of at least 120 million peasants to the Terror campaign and the “excess mortality” of between 6 and 13 million people such Terror caused during this period notwithstanding. By precisely which standards can this campaign have said to have been “successful”? The historian Catherine Evtuhov observes: “From any humane perspective, the terrible costs were far greater than the rewards.”33 In contrast, Jeremy and Justin either do not recognize the brutality of the Stalinist regime’s campaign, or they simply explain away mass-death during collectivization as resulting from natural disasters—thus ‘naturalizing’ the Soviet regime’s contributions to famines—and/or “kulak resistance.” By so easily dismissing mass-death, they imply that the millions of poor peasants who were destroyed as a result of forcible collectivization deserved such a fate.

Jeremy and Justin are very insistent on arguing that the deaths associated with collectivization were “not due” to Stalin’s policies—against both logic and evidence. They have nothing to say about Stalin’s reconstitution in 1932 of the Tsarist-era internal-passport system, or propiska, in order to tightly control the movements of the Soviet peasantry and proletariat during forced collectivization. Upon its proclamation in December 1932, such “passportization” was effected and mandated in “towns, urban settlements, district centers, and Machine and Tractor Stations, within 100-kilometer radiuses around certain large towns, in frontier zones, on building sites and state farms”: it thus openly revoked the freedom of movement of the majority of the Soviet population, including peasants and ethnic minorities.34 With this in mind, it would appear that the “Proles of the Round Table” do not to want to concede the possibility—and reality—that Stalin’s “dekulakization” campaign involved the oppression and dispossession of many poor peasants, whether these were insurgents against whom the State retaliated for defending their communities against Stalinist incursion or simply peasants whom the parasitic bureaucracy considered mere objects of exploitation and either killed outright or left to die during forcible collectivization—thus reflecting the extent to which internal colonialism characterized the Stalinist State.35

Indeed, Stalin’s “dekulakization” campaign followed a very clearly state-capitalist rationale, both requiring and (once established) providing mass-labor inputs. Based on the economic theory of Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, Stalin’s massive State project to centralize the peasantry so as to more deeply exploit it represented the phase of “primitive socialist accumulation” that was considered as necessary to finance a rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union. In parallel to the colonization of the New World, the enslavement of Africans, and the enclosure of the commons by which capitalism arose as a historical mode of production,36 Preobrazhensky essentially argued that the Soviet State must exploit the peasants and use the surplus value extracted from them to accelerate the growth of capital and industry.37 This brutally mechanistic logic, which has served as the model for similar industrialization processes in countries led by Stalinist bureaucracies such as Maoist China and Ethiopia under the Derg,38 openly exhibits Marxist-Leninism’s fundamental bias against the peasantry, whether “kulak” or otherwise. Such bias was clearly on display on Ó Séaghdha’s podcast, given the embarrassing side-comments about “comrades cuddling” during the horrors of forced collectivization, and Jeremy and Justin’s astonishing conclusion that this collectivization which took the lives of millions of poor peasants had been “extremely successful.” These Stalinists thus appear to have no class analysis of the peasantry, instead considering them all as reactionaries and “capitalists” whose oppression and destruction signifies progress. They malign the peasants and laugh over their corpses while saying nothing about the conditions of “second serfdom”—represented by barshchina (State labor requirements), extraction, and low pay—that formed the basis of Stalinist industrialization.39

Within Soviet class society, according to Voline (writing in 1947), there existed approximately 10 million privileged workers, peasants, functionaries, Bolshevik Party members, police, and soldiers (comprising approximately 6% of the population of the USSR/USCR), as against 160 million effectively enslaved workers and peasants (or 94% of the USSR/USCR’s population).40 The basic structure of the Soviet Union, on Paul Mattick’s account, was “a centrally-directed social order for the perpetuation of the capitalistic divorce of the workers from the means of production and the consequent restoration of Russia as a competing imperialist power.”41 This ‘total State’ “resembled an army in terms of rank and discipline,” and atop it all “lived Stalin, moving between his Kremlin apartment and his heavily guarded dachas. He and his cronies indulged themselves night after night, in between issuing commands and execution orders, feasting and toasting in the manner of gangland chiefs.”42

The meaning of forcible collectivization: child labor on an irrigation project in Fergana, Eastern Kazakhstan, 1935 (courtesy David Goldfrank)

4. The GULAG Slave-Labor Camp System

“The deaths of the conquered are necessary for the conqueror’s peace of mind.” – Chinggis Khan: a phrase of which Stalin was fond (Evtuhov 676)

His regime’s founding (in 1930), mass-expansion, and vast utilization of the GULAG slave-labor camp system, known officially as the “State Camp Administration,” which played a central role in the General Secretary’s “Great Purge,” otherwise known as his “Terror.” These purges served the goal of “ensur[ing] the survival of the regime and Stalin’s position as its supreme leader” by eliminating the remaining “General Staff of the [Russian] Revolution” as well as the workers, peasants, and intellectuals who resisted Stalin’s state-capitalist plans.43 The General Secretary’s insistence on obedience, his paranoid vengefulness, his equation of any kind of opposition with treason, and the fear felt by Communists that the Soviet Union was militarily encircled, particularly in light of a newly remilitarized and fascist Germany, can help explain the Terror, which involved the arrest of at least 1.5 million people, the deportation of a half-million to camps, and the execution of hundreds of thousands. The total camp population reached 2.5 million in 1950.44

As Yevgenia Semënovna Ginzburg’s memoir Journey into the Whirlwind attests to, the GULAG system was designed in such a way as to partially recoup the financial losses involved in the mass-imprisonments which followed from Stalin’s Purges of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union: instead of summarily being executed or idly rotting away in prison, many detainees were forced to work for the State with little to no material compensation. Ginzburg shows as well that political prisoners suffered greater discrimination in access to health services, nutritional intake, shelter, and types of labor performed in the GULAG, relative to other convict groups: the ‘politicals’ were always assigned hard labor. Many GULAG prisoners died performing slave-labor, whether clearing forests or constructing railroads: such was the fate of numerous enslaved prisoners forced to construct the Moscow-Volga Canal from 1932-1937.45 Within the Magadan camp located in Eastern Siberia where Ginzburg was held, the discrepancy between the housing conditions of Hut No. 8, a “freezing cold” “wild animals’ den” where the female political prisoners lived, and the abodes of those convicted for lesser offenses, in which lived individuals with “healthy complexions and lively faces” enjoying “blankets in check patterns” and “pillows with hemstitched linen covers,” clearly illustrates the discrimination.46 This same dynamic seems to explain the contrast in appearance—and physical comfort—among the female slave-labor teams assigned to the Kilometer 7 work site: the “peasant women” “had managed to keep their own coarse scarves” and some of the “ordinary criminals” had sheepskin coats, while the political prisoners “had not a rag of [their own]” and wore footwear which was “full of holes [and] let in the snow.”47 Ginzburg’s fellow inmate Olga was therefore right to anticipate that Stalin’s regime would expand the use of “hard-labor camps” in the wake of the downfall of NKVD head Nikolai Yezhov in 1939, especially considering that the majority of those imprisoned by Stalin were of prime working age.48

In a reflection of the maxims of Stalinist state-capitalism, Ginzburg reports that the slave-labor system to which she was subjected in the GULAG would dole out food only in proportion to the output that a given team would achieve. For teams like hers comprised of intellectuals and ex-Party officials who lacked experience with manual labor, then, this dynamic would result in a downward spiral of production—and welfare, since they were unable to achieve a basic threshold for production which would allow them access to the very food they needed to maintain and increase production in the future.49 Yet slave-laborers were sometimes provided with food relief if mortality rates were deemed ‘excessive.’50 Ginzburg’s memoirs thus suggest that, as far as political prisoners were concerned, the GULAG system was designed to torment such ‘politicals’ by maintaining them at a minimal level of sustenance, rather than starving or otherwise killing them outright.

On a more positive note, Stalin’s death in March 1953 brought “hope [to] the [inmates of the GULAG] camps,” inspiring both the June 1953 workers’ uprising against Stalinism, which not only overthrew State power in several cities and work-sites in East Germany but also involved workers’ liberation of prisons and concentration camps, and the unprecedented strike by political prisoners at the Vorkuta slave-labor camp which followed just two weeks later.51 Dunayevskaya comments in a manner that remains completely germane today that both of these episodes represented an “unmistakable affirmative” response to the question of whether humanity can “achieve freedom out of the totalitarianism of our age.”52

5. Assassination of Trotsky

“What specific characteristics in a man enable him to become the receptacle and the executor of class impulses from an alien class[…]?” – Raya Dunayevskaya53

His ordering of the assassination of Lev Trotsky, as carried out by the Spanish NKVD agent Ramón Mercader in Trotsky’s residence in Coyoacán, Mexico, in August 1940. Whereas there is little love lost between us and the “Old Man,” as Trotsky was known, given his status as the butcher of the Kronstadt Commune, the would-be executioner of Nestor Makhno, an advocate of the militarization of labor, and an apologist for State slavery54—still, Stalin’s brazen attempts to assassinate him in Mexico City not once but twice remain shocking in their brutality to this day. They may well have inspired the commission of similar atrocities on the part of the C.I.A.,55 the Israeli Mossad, and even Mohammed bin Salman’s recent murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

First, on May 24, 1940, the Mexican surrealist and muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros led an assassination-squad in an assault on Trotsky’s fortified family residence, which the exiled Bolshevik leader had been granted by Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas, who had afforded him asylum and personal protection. Mercader represented Stalin’s back-up plan. Having adopted an elaborate “deep-cover” false identity as “Jacques Mornard,” a Belgian aristocrat unconcerned with political questions, Mercader had seduced and used Sylvia Ageloff, herself a leftist Jewish intellectual from Brooklyn connected through her sisters to Trotsky, for two years to get close enough to facilitate both assassination attempts. While the complicity of “Jacques” in the first plot remained undetected, this was only possible because Siqueiros’ team captured and murdered Trotsky’s young American security guard Robert Sheldon Harte, whom Mercader knew and also used to gain access to Trotsky’s residence in the early morning of May 24. Yet a combination of luck; quick-thinking by Natalia Sedova, Trotsky’s wife, who isolated and shielded her partner’s body from the would-be assassin’s bullets; and the imprecise strategy to kill Trotsky that morning ensured his survival.56 Nevertheless, following a dry-run to assassinate Trotsky in his study using an ice-pick on the pretext of discussing a political article he had begun to write, Mercader invited himself back to Trotsky’s residence on the hot summer day of August 20, 1940, to discuss some revisions he had supposedly made to improve the same article. Concealing his ice-pick under a heavy raincoat, Mercader provoked Natalia Sedova’s suspicions about his presentation:

“Yes, you don’t look well. Not well at all. Why are you wearing your hat and raincoat? You never wear a hat, and the sun is shining.”57

Nevertheless, despite Natalia Sedova and Trotsky’s own intuitive misgivings, this Stalinist agent did ‘succeed’ in assassinating the exiled Bolshevik that day—precisely by burying an ice-pick into Trotsky’s head from behind, as the “Old Man” was distracted turning the page while reading the very essay Mercader had brought him:

“The moment was rehearsed. Wait until he finishes the first page, [NKVD officer] Eitington had coached. Wait until he is turning the page, when he will be most distracted.”58

What a fitting allegory for Leninism and Stalinism: conflict-resolution according to the principle of “might makes right.”59 Trotsky’s fate also openly displays Stalin’s anti-Semitism: in so ruthlessly murdering his primary political rival, a world-renowned Bolshevik leader and Jewish dissident,60 in Coyoacán, which lies approximately 6,000 miles (or 10,000 kilometers) from Moscow—after having exploited Sylvia Ageloff, a fellow Jewish intellectual, to gain access to the desired target—the “Man of Steel” flaunts his attitude toward the relationship between Jews and his false “Revolution.” Mercader’s assassination of Trotsky therefore illuminates the clear continuities between Stalin and the bourgeoisie, in terms of their shared instrumentalization of human life, and the “full-circle” development of the Russian Revolution, proving Voline’s point that “Lenin, Trotsky, and their colleagues [as Stalin’s predecessors] were never revolutionaries. They were only rather brutal reformers, and like all reformers and politicians, always had recourse to the old bourgeois methods, in dealing with both internal and military problems.”61

Notes

1Arendt 472.

2Elliott Liu, Maoism and the Chinese Revolution (Oakland: PM Press, 2016), 68).

3Evtuhov 697-698.

4Henry Wolfe, The Imperial Soviets (New York: Doubleday, 1940).

5Alfred Meyer, Communism (New York: Random House, 1984), 92-93.

6E. H. Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 2 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), 195-196.

7Dunayevskaya 318.

8Hensman 36.

9Olivier Roy, The New Central Asia: The Creation of Nations (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 52.

10Hensman 53-60.

11Eric Lee, The Experiment: Georgia’s Forgotten Revolution, 1918-1921 (London, Zed Books, 2017). See a review here.

12Ibid 160-166.

13Roy 50-51, 83.

14Ibid 50.

15Evtuhov 692.

16Roy 45-46, 52-53, 66.

17Ibid 64-65.

18Roy 67.

19Evtuhov 692.

20Roy 46, 68, 73.

21Dunayevskaya 318.

22Evtuhov 689-690.

23Hensman 88-89.

24This line is disturbingly close to that of the neo-fascist Aleksandr Dugin, who welcomed Russia’s 2014 invasion of Eastern Ukraine by calling for “genocide… of the race of Ukrainian bastards [sic].” Alexander Reid Ross, Against the Fascist Creep (Chico, Calif.: AK Press, 2017), 233.

25Plokhy 259.

26Wayne Price, Anarchism and Socialism: Reformism or Revolution? 3rd ed. (Edmonton, Alberta: Thoughtcrime, 2010), 186-189; Cornelius Castoriadis, “The Role of Bolshevik Ideology in the Birth of the Bureaucracy,” in Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrevolution, eds. Friends of Aron Baron (Chicago, Calif.: AK Press, 2017), 282.

27Voline, The Unknown Revolution (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1975), 359-361.

28Paul Mattick, “Bolshevism and Stalinism,” in Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrevolution, eds. Friends of Aron Baron (Chicago, Calif.: AK Press, 2017), 271.

29Voline 372-375.

30Evtuhov 670.

31Ibid 668; Voline 374.

32Evtuhov 668-669.

33Ibid 670.

34For a translation of the text of the December, 1932 decree of the USSR Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars, see M. Matthews, Soviet Government: a Selection of Official Documents on Internal Policy, J. Cape, 1974, 74-77.

35Hensman 34-35; Plokhy 249-250.

36Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (Penguin: London, 1976), 873-904.

37Evtuhov 642.

38Jason W. Clay and Bonnie K. Holcomb, Politics and Famine in Ethiopia (Cambridge, Mass.: Cultural Survival, 1985).

39Evtuhov 685.

40Voline 380, 388.

41Mattick 264.

42Evtuhov 688, 730.

43Plokhy 255; Dunayevskaya 320.

44Evtuhov 671, 676, 693, 730.

45Ibid 675, 688.

46Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg, Journey Into the Whirlwind, trans. Paul Stevenson and Max Hayward (San Diego: Harcourt, 1967), 366, 368.

47Ibid 402.

48Ibid 258.

49Ibid 405-406.

50Ibid 415.

51Dunayaevskaya 325-329.

52Ibid 327-329.

53Ibid 317.

54Ida Mett, “The Kronstadt Commune,” in Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrevolution, eds. Friends of Aron Baron (Chicago, Calif.: AK Press, 2017), 185-190; Voline 592-600; Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control (London: Solidarity, 1970).

55Arendt xxn4.

56John P. Davidson, The Obedient Assassin (Harrison, NY: Delphinium Books, 2014), 48, 193-199.

57Ibid 274.

58Ibid 276.

59Voline 374.

60A dissident relative to Stalinism in power, that is, but not relative to anarchism or libertarian communism.

61Voline 431-432 (emphasis added).

Tags:"Proles of the Round Table, Abyssinia, Adolf Hitler, Afghanistan, Amanullah Khan, anti-Semitism, AR, Armenia, Assad Regime, ASSR, autogestion, Azerbaijan, barshchina, Bashar al-Assad, Basmachi, bazaars, bourgeoisie, Breht Ó Séaghdha, Buddhists, campism, caravans, Catherine Evtuhov, Central Asia, chauvinism, child labor, China, Chinggis Khan, CIA, Comintern, concentration camps, Coyoacán, David Alfaro Siqueiros, deportations, Derg, dual bridgehead, Dushanbe, Eitington, enslavement, Ethiopia, ethnic minorities, Evtuhov, famine, Fergana, forced collectivization, forced labor, forcible collectivization, Georgia, Georgian Commune, Great Purge, GULAG, Guomindang, Hannah Arendt, high modernism, Hitler, Hitler-Stalin Pact, Holodomor, Ibn al-Sa'ud, imperialism, indigenous, instrumentalization of human life, intellectuals, internal passport system, Iran, Islam, Jacques Mornard, Jamal Khashoggi, Josef Stalin, Journey into the Whirlwind, Justice for Jamal, Kazakhstan, Kilometer 7 work site, kolkhozi, Kremlin, Kronstadt, Kronstadt Commune, kulak, Kurds, Lázaro Cárdenas, Lebensraum, Lenin, Lev Trotsky, LGBT Pride, Mao Zedong, Maoist China, mass-deportations, May Days, México, MBS, Mensheviks, Meskhetians, Mexico City, might makes right, Mohammed bin Salman, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Moscow, Moscow-Volga Canal, Mossad, Muslims, Mussolini, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Natalia Sedova, National Bolshevism, nationalism, Nazi-Soviet Pact, neo-fascism, NEP, New Economic Policy, New World, Nikolai Bukharin, Nikolai Yezhov, NKVD, NT, самоуправление, Old Man, pan-Islamism, pan-Turkism, patriarchy, peasants, permanent revolution, Peter Stolypin, Preobrazhensky, primitive socialist accumulation, propiska, Ramón Mercader, Raya Dunayevskaya, Right Sector, Robert Sheldon Harte, Saudi Arabia, second serfdom, self-determination, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, settler-colonialism, slave labor, social democracy, social fascism, socialism, socialism in one country, solidarity, sovkhozi, SSR, Stalin, Stalinabad, Stalinism, state capitalism, Sultan Galiev, Svoboda, Sylvia Ageloff, Tajikistan, Tajiks, terror, Third International, Trotsky, Trump Regime, Turkestan, Turkey, Ukraine, ultra-nationalism, Ummah, USCR, USSR, Uzbeks, Vladimir Lenin, Volga Germans, Volga Tatar, Vorkuta camp, Vorkuta strike, War Communism, workers, Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, Yevgenia Semënovna Ginzburg

Posted in 'development', Afghanistan, Africa south of the Sahel, audio, China, displacement, Europe, fascism/antifa, health, imperialism, Imperiled Life, Iran, Kurdistan, México, reformism, requiems, Revolution, Russia/Former Soviet Union, Shoah, U.S., Ukraine, war | 1 Comment »

From the archives: “For a different world,” from a draft of Imperiled Life (Sept. 2011)

September 14, 2018

Images courtesy @SyriaRevoRewind

I am pleased to share this section from a draft of Imperiled Life: Revolution Against Climate Catastrophe, which examines contemporary revolution and repression in a few Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries. It was finished on September 11, 2011. Had they been included, these reflections would appear at the bottom of p. 171 of the book as it is. I welcome feedback and criticism in the comments section below. Please note that the images used above are not necessarily contemporary to the timing of this writing [e.g., the Douma Four were disappeared in December 2013].

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, it should be said, has played a thoroughly counter-revolutionary role to the so-called Arab Spring, in accordance with its own interests and those of the U.S. it serves. This has been seen in its pushing within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) for a conservative resolution of the delegitimization experienced by Ali Abdullah Saleh’s regime in Yemen since mass-mobilizations arose there in the wake of Mubarak’s fall, but it is expressed most starkly in the KSA’s invasion of the island-state of Bahrain following the birth there of a mass-protest movement against the al-Khalifa ruling family in early 2011. The movement has since been suppressed, with Manama’s Pearl Square—the common at which protesters met to mobilize—physically destroyed and protesters detained and prosecuted, in standard operating procedure. It seems the KSA in part fears the mobilization of Bahrain’s Shi’a could be replicated among the Shi’a minority residing in eastern Saudi Arabia, where most of the country’s oil resources are located; it may also fear the the model of solidarity observed among Sunni and Shi’a protesters in Bahrain. The billions given in a welfare package prepared by the House of Saud for workers to stave off is one with their purchasing of billions of dollars of arms from the U.S.

In the case of Libya, developments have been more negative than elsewhere. Given the very real ties between the Qaddafi regime and Western powers since 2003—intelligence-sharing between Libya and Western governments, oil contracts with Western corporations, and Qaddafi’s brutal mass-detention of African migrants traversing Libya en route to Europe—the sudden commencement of NATO military operations against Qaddafi in March 2011 struck [me] as somewhat puzzling. By now, though Qaddafi has fallen and the Transitional National Council has taken power, it should be clear that Western intervention in the country has little to do with humanitarianism. That Western officials say not a word of the forced displacement and massacres of black African migrant workers as prosecuted by the Libyan ‘rebels’ is a comment on their humanity, as are the deaths at sea of hundreds of such workers, attempting to flee ‘the new Libya.’ For its part, the stock market welcomed the taking of Tripoli by oppositional forces.

The situation in Syria is bleak as well. Since the beginning of protests in the country in March 2011, Ba’ath President Bashar al-Assad has overseen an entirely obscene military-police response aimed at employing force against those calling for his fall. Unrest in Syria reportedly began with the detention of youths who authored graffiti reproducing the cry that has animated subordinated Arabs throughout this period of popular mobilization: “Al-sha’ab yourid isqat al-nizam!” (“The people want to overthrow the regime!”) The deployment of government tanks and infantry units in cities throughout the country in recent months has resulted in the murder of some 2,300 regime-opponents and the imprisonment of another 10,000. The regime’s defensive tactics, borrowing from Saleh in Yemen and Mubarak loyalists in Tahrir, have been more ruthless still than in these cases, for Assad’s security apparatus has engaged in near-daily attacks on assembled crowds and funerary processions as well as the use of naval barrages against coastal settlements. It is unknown precisely what political currents unify the Syrian opposition other than calls for Assad’s resignation, but it is self-evidently comprised at least in part by anti-authoritarians. In contrast to the case in Libya, or at least among those Benghazians heard by Western powers, Syrian dissidents are strongly opposed to the prospect of Western military intervention against Assad’s brutality. In this belief, as in the various mutinies reported among soldiers opposed to the commands demanded by Assad’s commanders, the Syrian example is an important one, however bleak the future if Assad’s military hangs on.

Though Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has reportedly called on Assad to halt the repressive tactics, it is undeniable that Assad’s response to protests has been informed by the Islamic Republic’s attempts at suppressing protests emanating from the Green movement from the 2009 presidential elections to the present. The Greens, of course, hardly represent a reasonable political progression beyond the conservatism of Ahmadinejad: their adulation of Mir Hossein Mousavi, prime minister during the Iran-Iraq War who oversaw mass-execution of leftist dissidents in the years following the 1979 revolution against the Shah, perpetuates myth,1 as does their advocacy of the suspension of public subsidies for materially impoverished Iranians. There seems to be little sense among Iranian reformists that the Islamic nature of the post-1979 regime is to be called into question—parallels with post-1949 China are found here. Perhaps a return to the perspectives advanced by Ali Shariati in the years before 1979 could aid subordinated Iranians in overturning that which Marxist critic Aijaz Ahmad terms “clerical fascism” in Iran.

1[An allusion to Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin’s analyses; “myth” here can be understood as the general oppression of an unenlightened, non-emancipated world.]

Tags:Aijaz Ahmad, al-Khalifa, Ali Abdullah Saleh, Ali Shariati, Assad, Bahrain, Bashar al-Assad, China, GCC, Hosni Mubarak, Iran, Islamic Republic of Iran, KSA, Libya, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, migrants, Mir Hossein Mousavi, Muammar Qaddafi, NATO, Saudi Arabia, Shia, Syria, Tahrir Square, Theodor Adorno, Tripoli, Walter Benjamin, Yemen

Posted in 'development', anarchism, displacement, Europe, health, imperialism, Imperiled Life, Iran, Iraq, literature, Revolution, Syria, U.S., war | Leave a Comment »

On Internationalist Socialist Solidarity and Anti-Imperialism

August 27, 2018Presentation at Left Coast Forum panel on imperialism and anti-imperialism, August 25, 2018

In light of the fate of the Syrian Revolution, which has now nearly been crushed entirely by the bloody counter-revolution carried out by Bashar al-Assad together with his Russian, Iranian, and Lebanese allies, there has been renewed debate on the global left regarding the meanings of imperialism and anti-imperialism, and the political implications these carry. Many authoritarians claiming leftism cross-over with the white-supremacist right’s open support for the Assad Regime by denying its crimes and overlooking the (sub)imperialist roles played by Russia and the Islamic Republic of Iran in Syria, focusing exclusively on the U.S.’s supposed opposition to Assad’s rule.

This tendency is a worrisome development, suggestive as it is of a red-brown alliance (or axis) that is not consistently anti-imperialist or internationalist but rather, only opposed to U.S. imperialism. It also fails analytically to see how the U.S. has increasingly accommodated Assad’s ghastly ‘victory,’ as reflected in Donald Trump’s cutting off of the White Helmets in May and his non-intervention as Assad, Russia, and Iran defeated formerly U.S.-supported Free Syrian Army (FSA) units of the Southern Front, reconquering Der’aa, birthplace of the Revolution, and the remainder of the southwest last month. In stark contrast to such approaches, today we will discuss militarism and imperialism from anti-authoritarian and class framework-analyses.

Toward this end, I want to suggest that Black Rose/Rosa Negra Anarchist Federation’s definition of imperialism is apt: from their Point of Unity on Internationalism and Imperialism, “Imperialism is a system where the state and elite classes of some countries use their superior economic and military power to dominate and exploit the people and resources of other countries.”1 This brutal concept applies clearly to contemporary and historical global practices which since 1492 primarily Western European and U.S. ruling classes have imposed onto much of the world, from the trans-Atlantic slave trade—this month marks 500 years—to colonial famines, genocide, military occupation, and settler-colonial regimes. Yet, more controversially among many so-called leftists who adhere to a ‘campist analysis,’ whereby the world is split up into competing military blocs,2 this concept of imperialism and its related concept of sub-imperialism can also be applied to the contemporary practices of the ruling classes of such societies as Russia, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa, otherwise known as the BRICS. According to Rohini Hensman in her new book Indefensible: Democracy, Counter-Revolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism (2018), the “pseudo-anti-imperialists” of today can be divided into three categories: tyrants, imperialists, and war criminals; the neo-Stalinists who openly support them; and Orientalist ‘progressives’ who focus exclusively on Western imperialism, to the exclusion of all other considerations, such as the agency of Middle Eastern peoples, as well as the realities of non-Western imperialism & sub-imperialism (47-52). For those to whom the concept may be unfamiliar, sub-imperialism is defined in the Marxist theory of dependency (MTD) as a process whereby a dependent or subordinate country becomes a “regional sub-centre,” unifies “different bourgeois factions by displacing internal contradictions, develops a “specific national and sub-imperialist political-ideological project,” forms and advances monopolies, and simultaneously transfers value to the core-imperialist countries while also exploiting materially and geopolitically weaker countries for the benefit of its bourgeoisie.3

The central military roles played by Putin and the Islamic Republic in rescuing the Assad Regime from defeat in the Syrian Revolution—and, indeed, their joint responsibility for the overall murder of 200,000 civilians and the forcible disappearance of over 80,000 Syrians in this enterprise over the past seven years, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), and as confirmed recently by Assad’s mass-release of death notices for detainees—thus starkly demonstrate pressing cases of imperialism and sub-imperialism on today’s global stage, yet in contrast to the struggle between Israel and the Palestinians just across Syria’s southwest border, it is apparently eminently controversial among U.S./Western neo-Stalinist ‘leftists’ to acknowledge the reactionary, authoritarian, and yes, (sub)imperialist functions served by Vladimir Putin and the Islamic Republic in propping up Assad,4 a neo-fascist who does not just rule over a ‘dictatorial regime’ but rather heads an exterminationist State, as the Syrian communist Yassin al-Hajj Saleh observes, and as the death toll attests to. According to Saleh:

“I do not talk about Syria because I happen to come from this country afflicted with one of the most brutal ruling juntas in the world today, nor because Syria is under multiple occupations while Syrians themselves are scattered around the world. Rather, I speak of Syria because the Syrian genocide is met by a state of global denial, where the left, the right, and the mainstream all compete with one another to avert their eyes and formulate cultural discourses, genocidal themselves, to help them see and feel nothing.”

The Russian Defense Ministry just announced on Wednesday, August 22, that 63,000 soldiers have fought in Syria in the past three years, while in June, Putin announced that Russian troops were “testing and training” in Syria so as to prevent a similar situation arising in Russia proper. (Does this sound to anyone like Dick Cheney talking about Iraq?) Hence, in light of the effective occupation of Syria perpetrated by Russia, Iran, Hezbollah, and other Shi’a militias (e.g. Liwa Fatemiyoun) to prop up the regime, taken together with their attendant contributions to what Saleh calls the Syrian genocide—a counter-insurgent reaction which others have termed ‘democidal’—it is my view, and I believe that of my co-panelists, that several of the struggles against Assad, Putin, and the Islamic Republic of Iran form critical parts of the global anti-imperialist movement which by definition resists militarism and regional and transnational domination and exploitation. If human rights are the “tribunal of history” and their end (or goal) the construction of an ethical and political utopia,5 these regimes, in parallel to Western imperialism, are on the wrong side of history. In accordance with the conclusion of Hensman’s book, democratic movements like the Iranian popular revolts of early 2018; the ongoing Ahwazi mobilizations for socio-ecological justice; those of feminists and political prisoners in all three countries; and Russian Antifa, among others, demand our support and solidarity as socialists. Of course, anti-imperialist forces should continue to oppose established Euro-American imperialism and settler-colonialism—“the main enemy is at home,” as Karl Liebknecht declared in 1915, denouncing what he termed the ‘genocide’ of World War I6—together with the neo-colonial crimes of allied autocracies such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in Yemen today. Liebknecht’s statement notwithstanding, we must recall that he in no way supported the Tsar or other imperialist rivals of the German State, but the Russian Revolution instead.